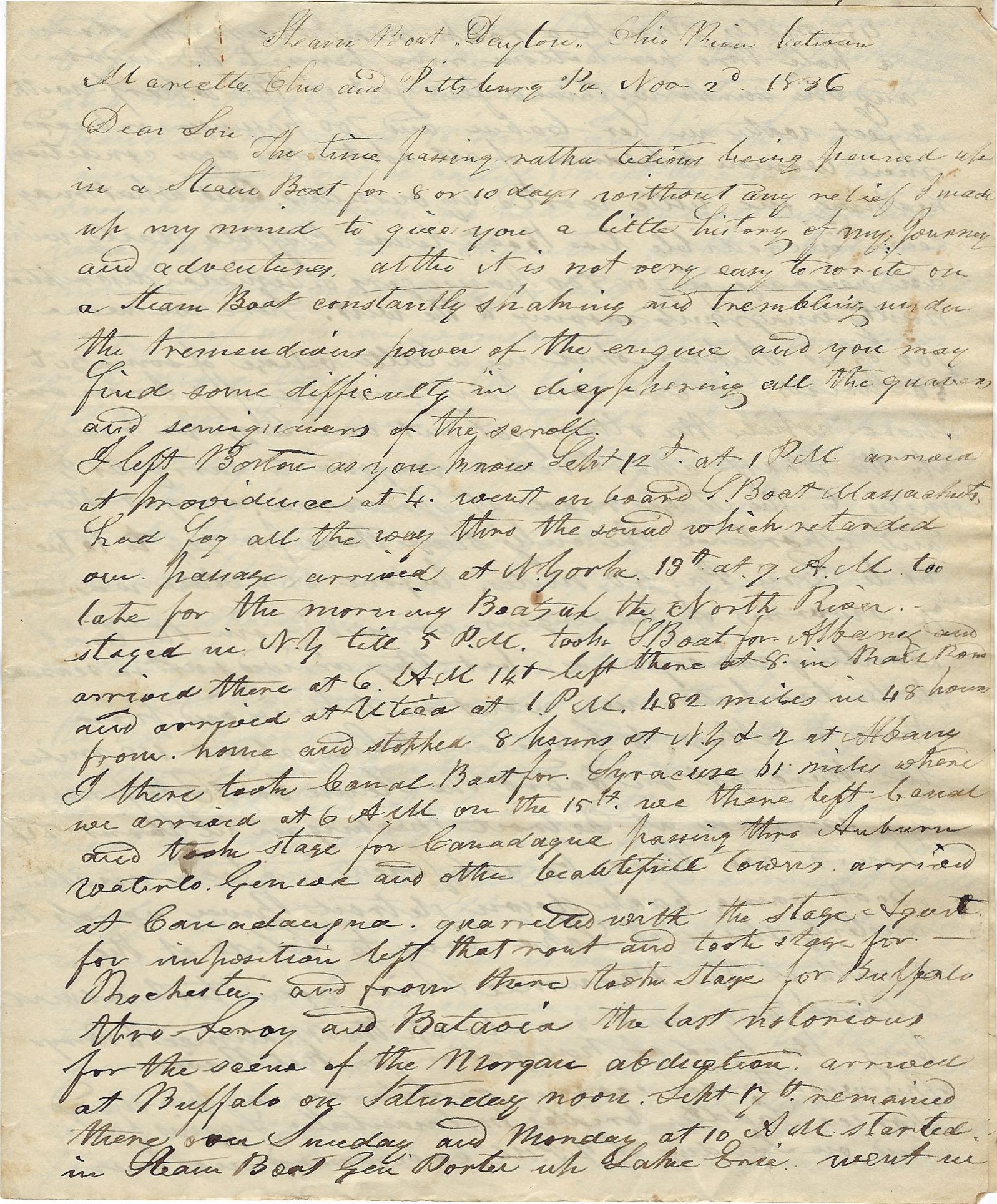

In this third and final installment, the illustrious Colonel Fay leaves St. Louis and heads back to Boston, though not without further misadventures and having witnessed a dreadful accident. As we join this episode, our hero is still hugely weakened but slowly recovering from a bout of something akin to rheumatic fever…

November 3rd on the Ohio River at anchor near Beaver 32 miles from Pittsburgh.

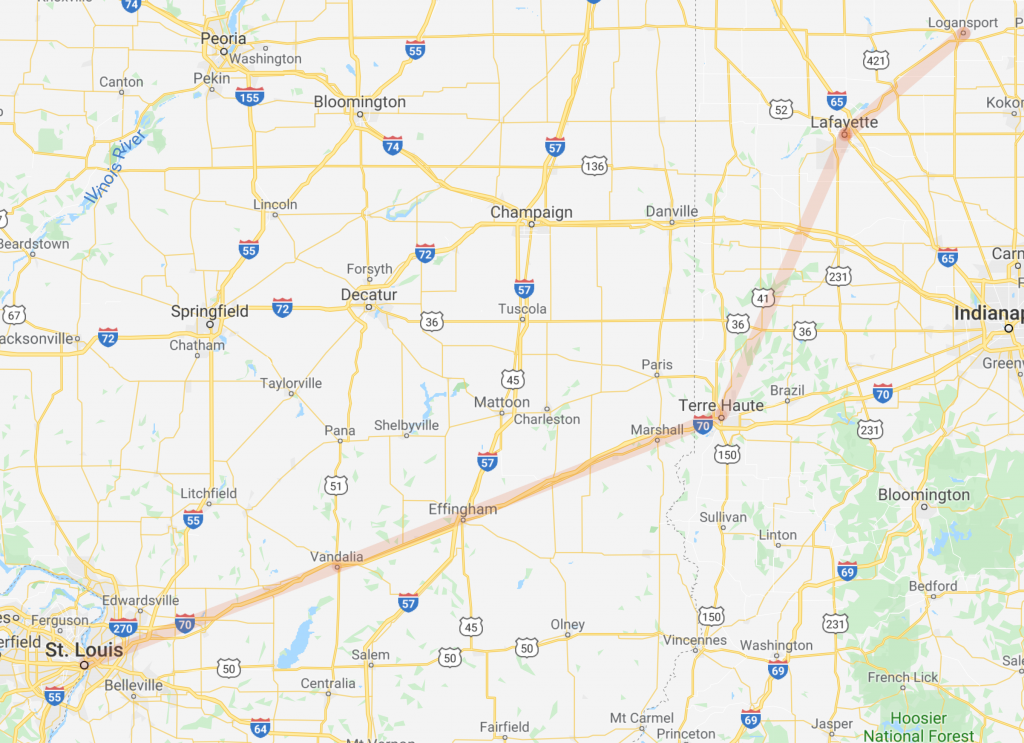

I resume my story as we are now unable to run owing to the darkness of the night and the narrow and crooked river here. And I come now to write without the continual shake I was subjected to when the boat was underway. I left St. Louis October 26th 10 AM perhaps before my health would justify it but one gains strength so slow in this country and I was so anxious to get home and have a New England diet and New England nursing that I ventured although I was just able to set up through the day.

I left in the steamboat Swift Boy and paid $25 for passage to Pittsburgh. They brought us to Cincinnati Ohio 750 miles out of 1300 and refused to carry us any farther or make any provision for us and insisted in taking $18 out of the 25 which we had paid although the regular price from St. Louis to Cincinnati was $15.

We quarreled awhile and I took the lead. I finally told the captain that I did not wish to quarrel, that he had undertook to carry us to Pittsburgh and we had paid him his price; he had not fulfilled his engagement and he was bound to carry us there or refund sufficient to carry us there, and that for one I should take no less, but should seek my [recourse] in some other way. He said we need not think to “scare him.” I answered that we had no idea of scaring; that I should not resort to a legal remedy although I supposed I had one. But that I should not spend 10 dollars to get 3; but that I had the right and should exercise that right of publishing the imposition to the world as a caution to the public not to travel on his boat. I then left him. In a few moments, the captain called us into the office and paid us back $10 each for the price of passage to Pittsburgh.

We then went immediately on board the Dayton where we have every accommodation [illegible]. We live like lords. My health is very much improved, my appetite good and I feel comfortable except that I want exercise. Being bound up 10 or 12 days in the cabin of a steamboat with 50 passengers is no pleasant affair. We shall probably arrive at Pittsburgh about noon tomorrow and and at 9 PM take the canal boat for Philadelphia.

Canal Boat Chesapeake on the Pennsylvania Canal near Mifflin, Juniata County Pennsylvania November 7th 1836

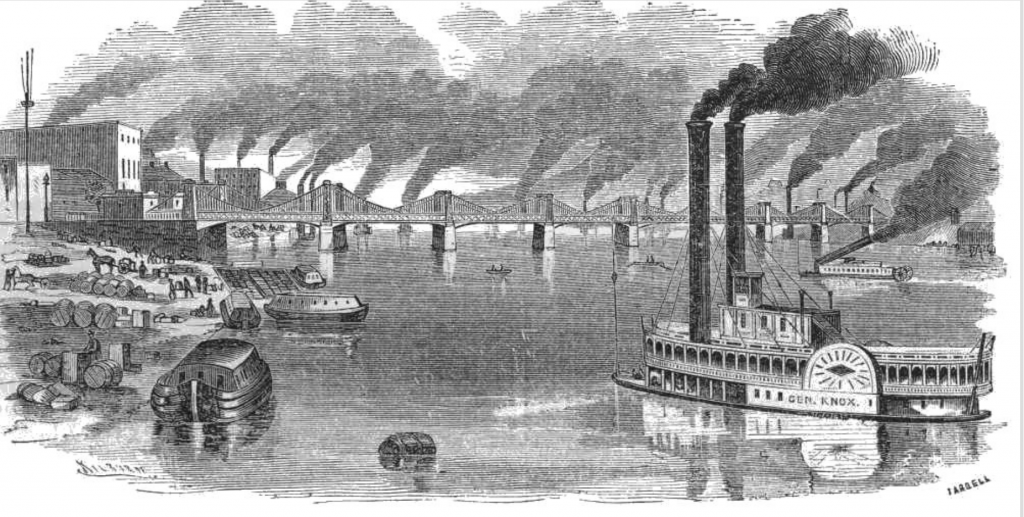

We arrived at Pittsburgh as I expected and found it one the most [illegible] unpleasant smoking towns I ever saw. It contains in its immediate suburbs about 40,000 inhabitants. It is situated at the junction of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers which here unite and form the Ohio. It is built on the spot where the French Fort Duquesne and afterward the English Fort Pitt was erected. It is surrounded by high mountains which almost completely enclose it on all sides.

[The town sits] upon a flat [and] is tolerably laid out and has many good buildings, but the numerous manufacturing establishments which are there erected and which burn coal, which is found in great abundance in the mountains within a half a mile of the town, means the town is covered with such a perpetual smoke that it completely prevents the atmosphere from being clean and all the buildings and inhabitants to carry the appearance of a smoke house. It is however a place of great business and considerable wealth and is fast increasing.

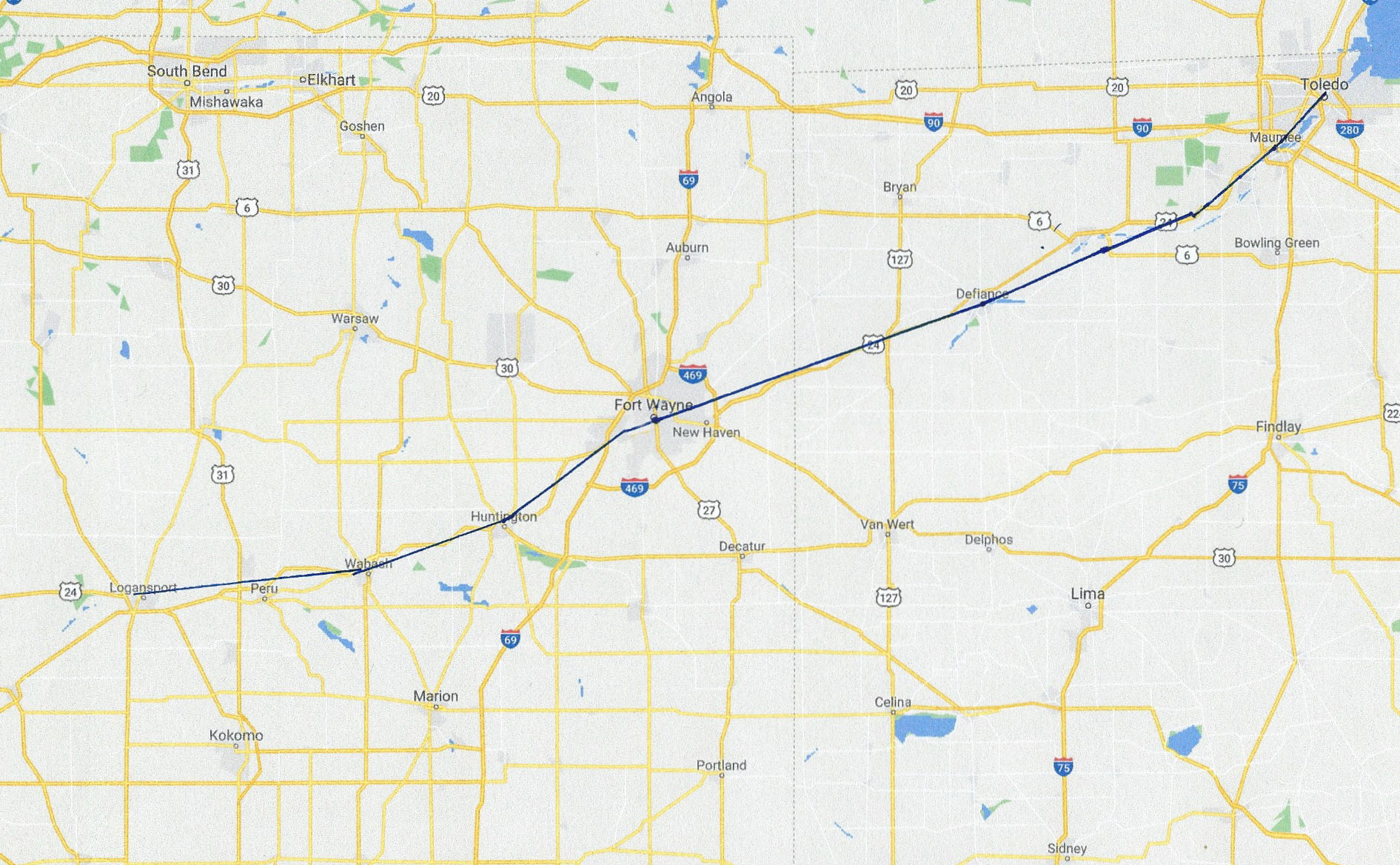

We left Pittsburgh at 9 PM on the 4th in the canal boat Niagara on the canal and on the 5th passed through a tunnel cut under the mountain through a solid rock nearly 1000 feet [long], sufficiently wide and deep for the canal boat—and the mountain some 200 feet over our heads.

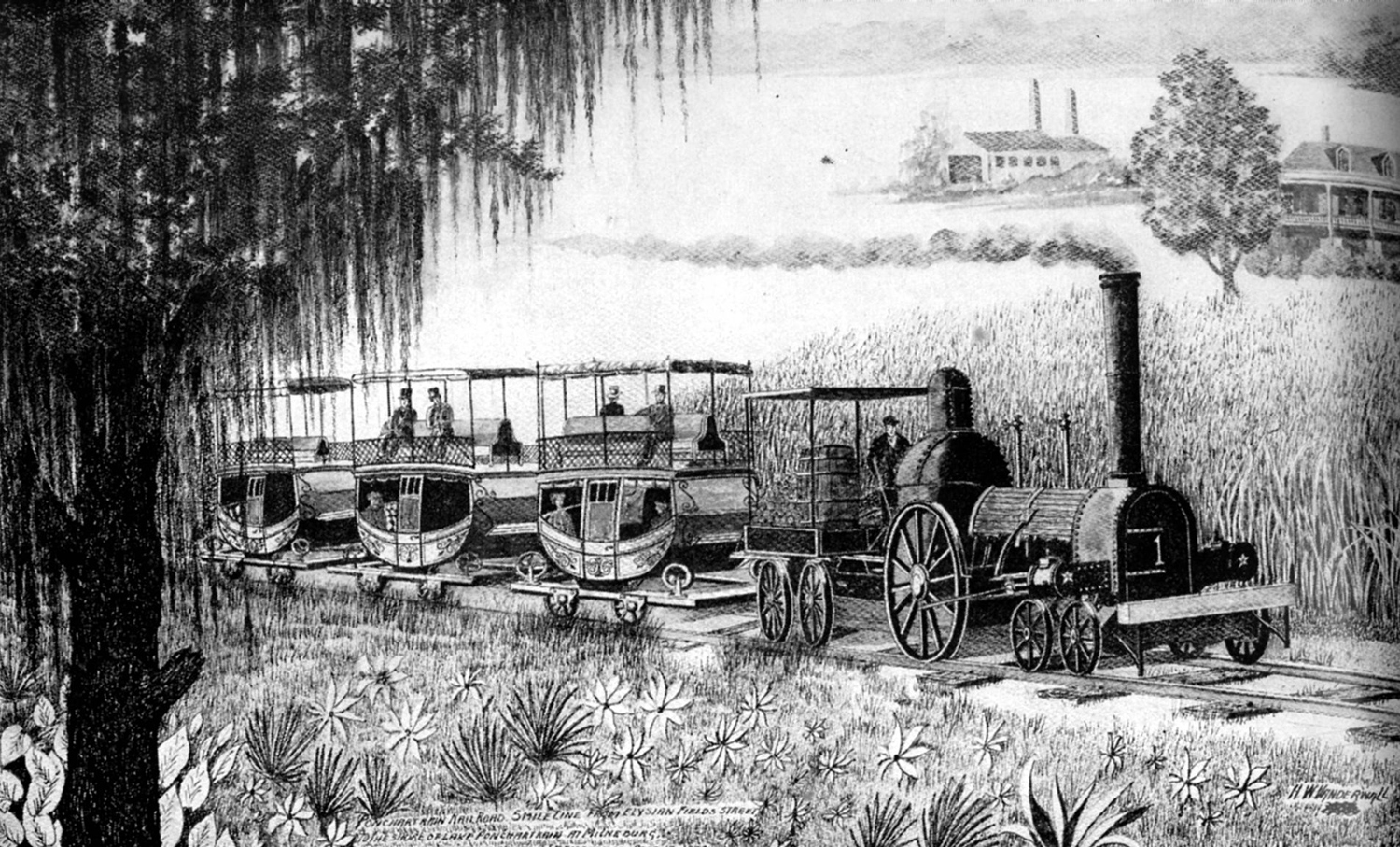

Soon after passing through the tunnel we came to the end of this canal, 106 miles, and to the Portage Railroad at Johnstown and in the course of the 16 miles ascended 5 incline planes of about ½ mile each in length and a rise of about 15 degrees to the top of the Allegheny Mountain and through another tunnel under a mountain equal with the one encountered before on the canal. We there commenced descending and in the same distance descended 5 more times of about the same descent but somewhat longer, and there were carried 4 miles without any power down such a gentle plain that the cars were propelled by their own weight to Hollidaysburg. We were then towed up and down these plains by stationary engines on each.

At Hollidaysburg we again took the canal in the boat which I now am and shall go down the banks of the Juniata River and Susquehanna to Columbia, 172 miles passing through Harrisburg the capital of Pennsylvania. At Columbia, we shall again take the railroad for Philadelphia, 82 miles.

We arrived at Columbia at 9 Am and stayed until 2 PM and took the cars for Philadelphia. When about half way a passenger was standing on top of the car in which I was seated and being careless came in contact with a bridge across the railroad when we were going about 20 miles an hour which struck his head and he fell upon the car dreadfully mangled.

We carried him about three miles to a public house and laid him upon a settee, and let him down and carried him into the home alive but perfectly insensible where we left him and he probably lived but a few hours if he did so long.

We came the rest of the way in the night and arrived in Philadelphia about 9 PM after being let down another long inclined plane of 5/8 of a mile to the Schuylkill River. I left Philadelphia the next day at 10 AM and arrived at New York at 6 PM by steamboat to Bordentown; railroad to South Amboy; and then by boat from there to New York. I left New York at 4 PM the next day in the steamboat Massachusetts, arrived at Providence a quarter before eight the next morning and took cars for Boston where I arrived.

FINIS

Remember: History like this doesn’t save itself. Please consider donating to the Southborough Historical Society. It’s quick, secure and easy.