Dear Friends,

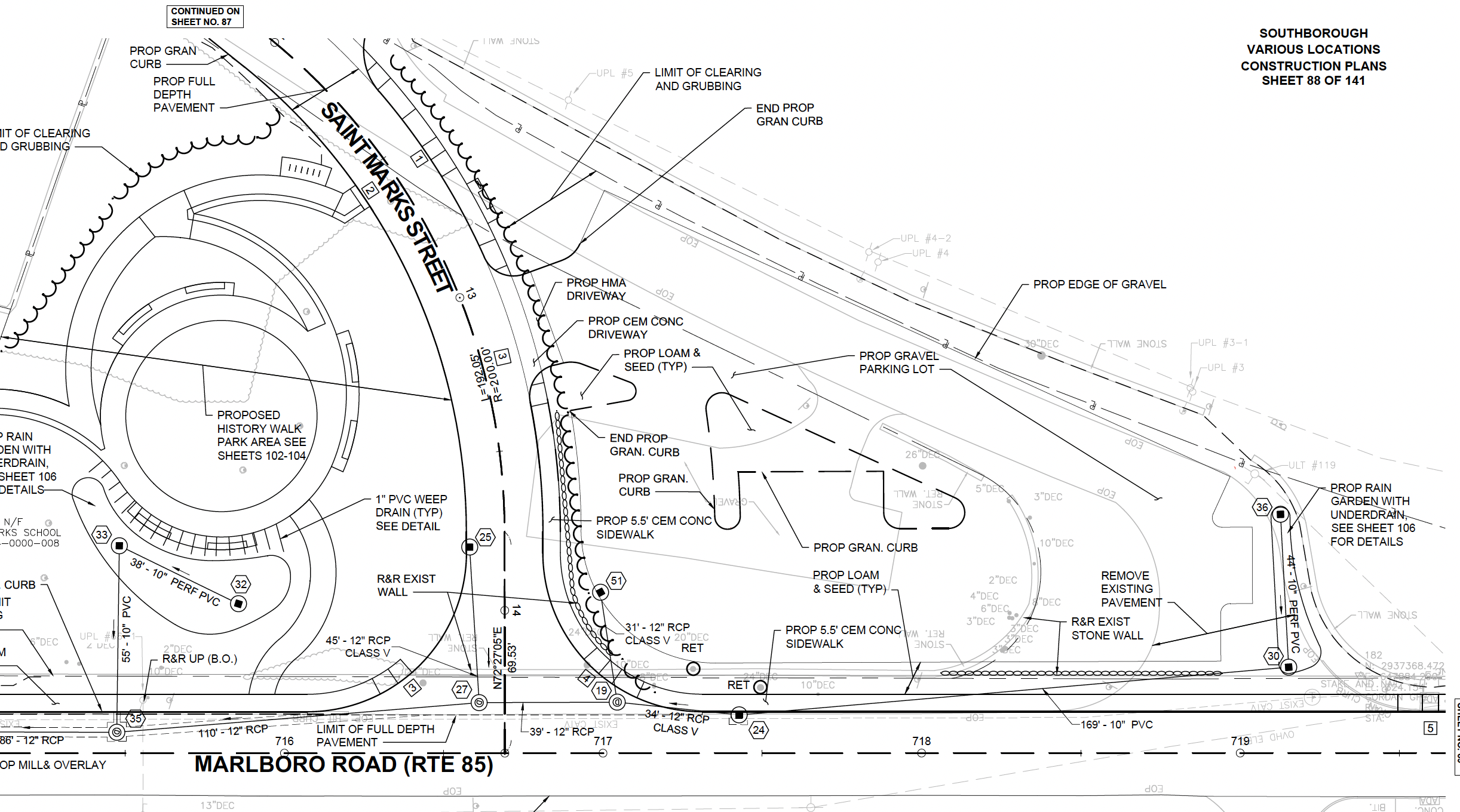

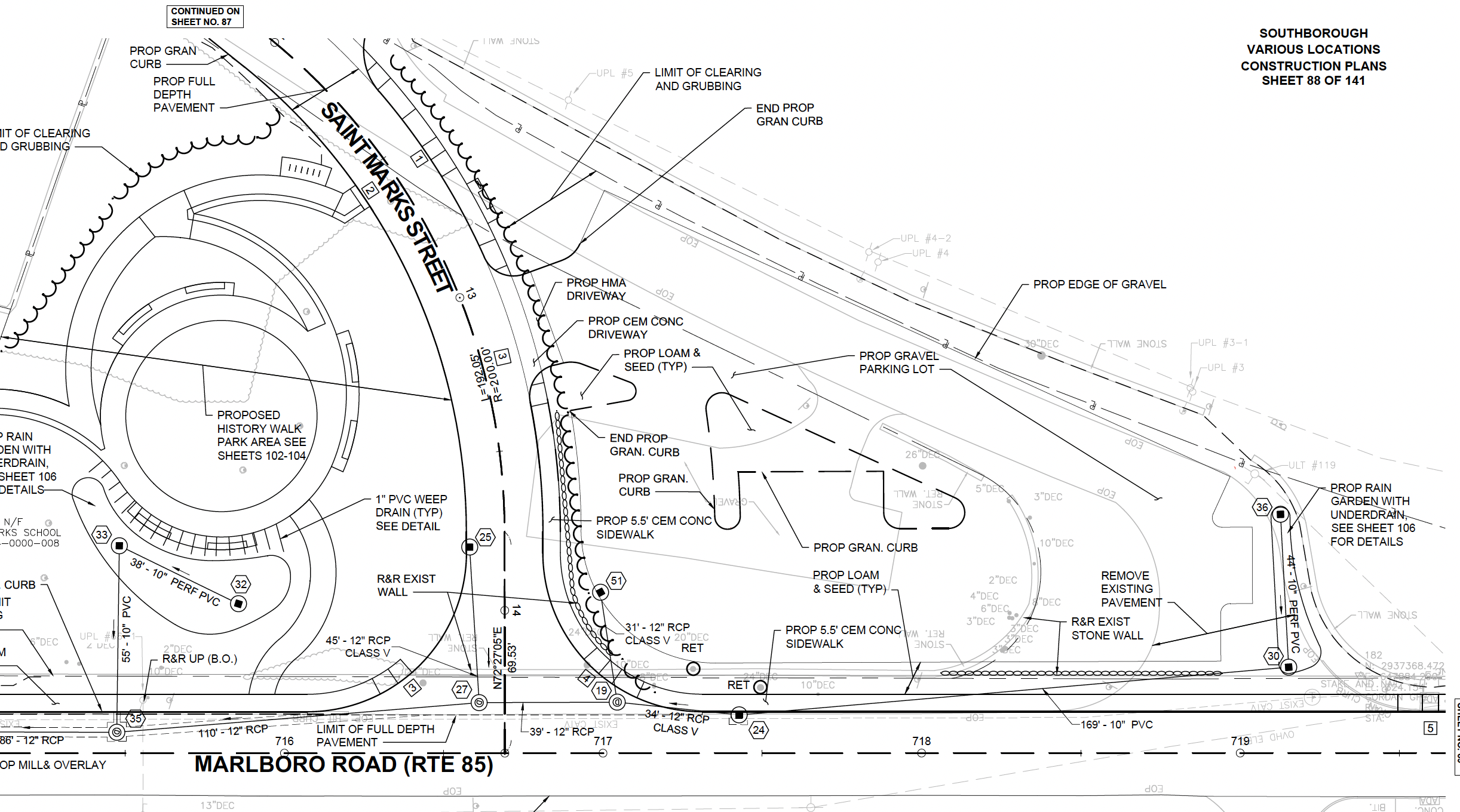

I would like to share with you a letter I wrote to the relevant Town Board and state agencies as Chair of the Historical Commission regarding the wholesale clear-cutting of the parcel adjacent to the Old Burial Ground. Though this parcel is entirely owned by St Mark’s, the town has apparently reached some license agreement—vetted by neither the Planning Board or the Historical Commission, to reroute St. Mark’s street in order to enhance the sports parking area for the school and create a pocket park. Apparently, the Town is using state funds to do this project, and St. Mark’s is paying for some?—though who is paying for what remains unclear at this point. Unfortunately, this ill-conceived project threatens to unearth human remains and has now destabilized the entire remaining Old Burial Ground tree cover.

To: Southborough Select Board; Southborough Planning Board; Southborough Open Space Commission; The Southborough Historical Commission; Mark Purple, Southborough Town Administrator; Brona Simon, Executive Director, Massachusetts Historical Commission and State Archeologist; Southborough Historical Society; Karen Galligan, Southborough Director of Public Works.

1 November 2021

As chair of the Historical Commission, I am writing to express extreme concern about the current road and park project along St. Mark’s street at the corner of Marlborough Road (Rte. 85).

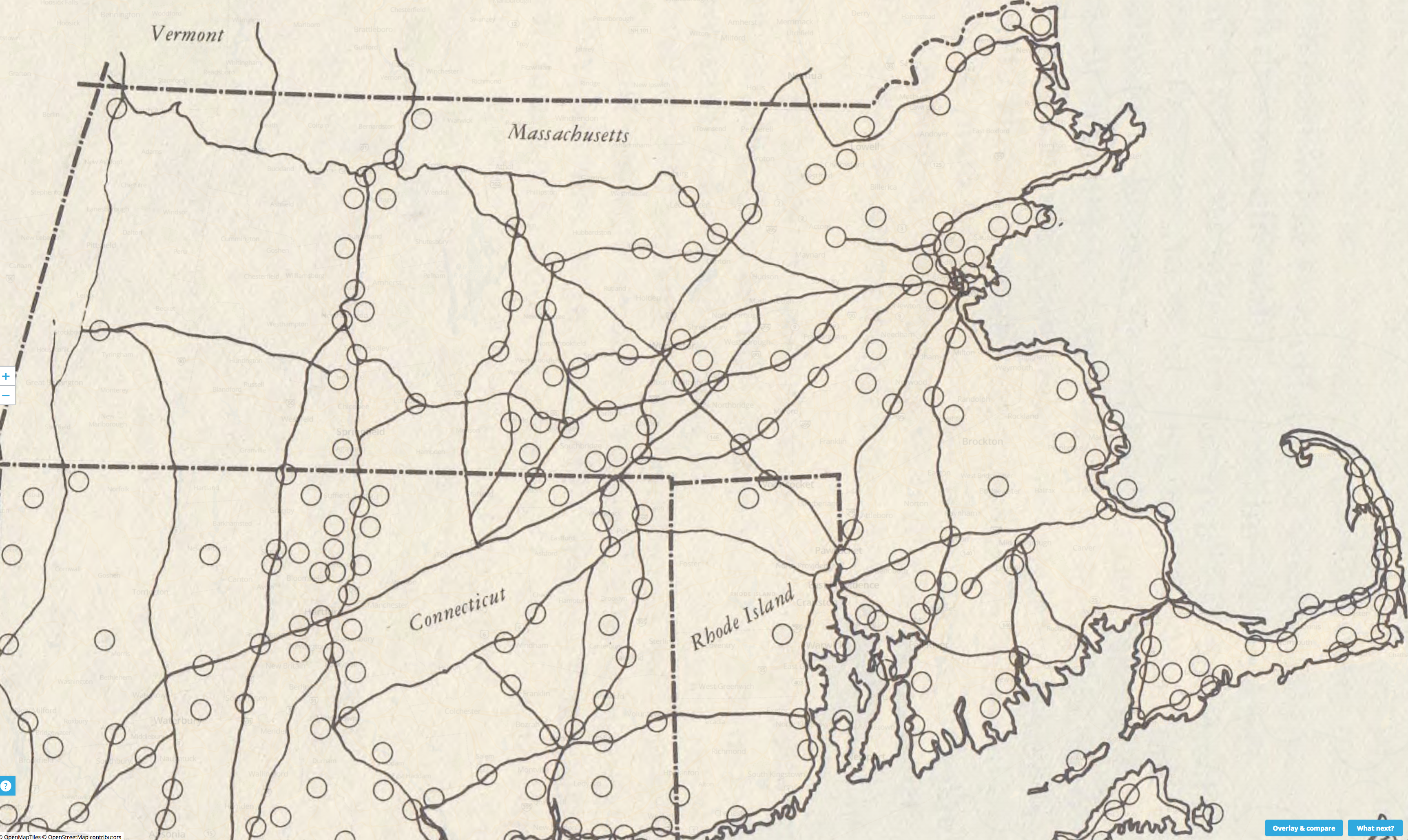

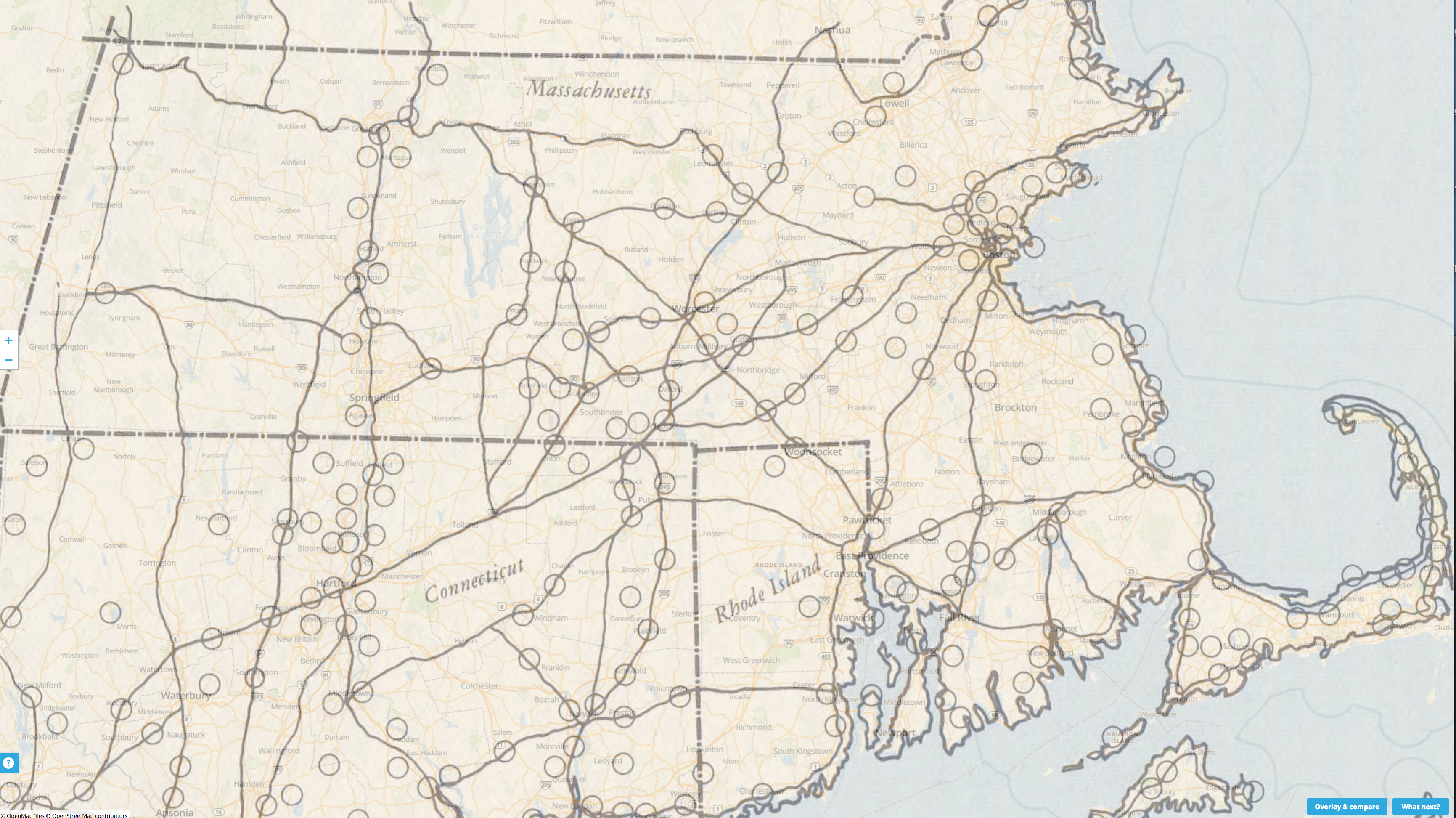

Although the Southborough Historical Commission had seen some conceptual plans for a park and history-walk back in the spring, we had not heard about it since, and presumed the project dead. Suddenly last week, the entire triangle bordering the Old Burial Ground, Cordaville Road, and St. Mark’s Street was clear-cut over a period of two days, without consulting either the Historical Commission or seeking the required Planning Board site review and approval. After speaking with Karen Galligan, the DPW head, it now seems that the project is proceeding using only a conceptual plan, with major elements such as the history-walk and playground arbitrarily deleted. With the educational and entertainment features eliminated, what exactly is the point of this project except facilitating expanded parking for St. Marks School?

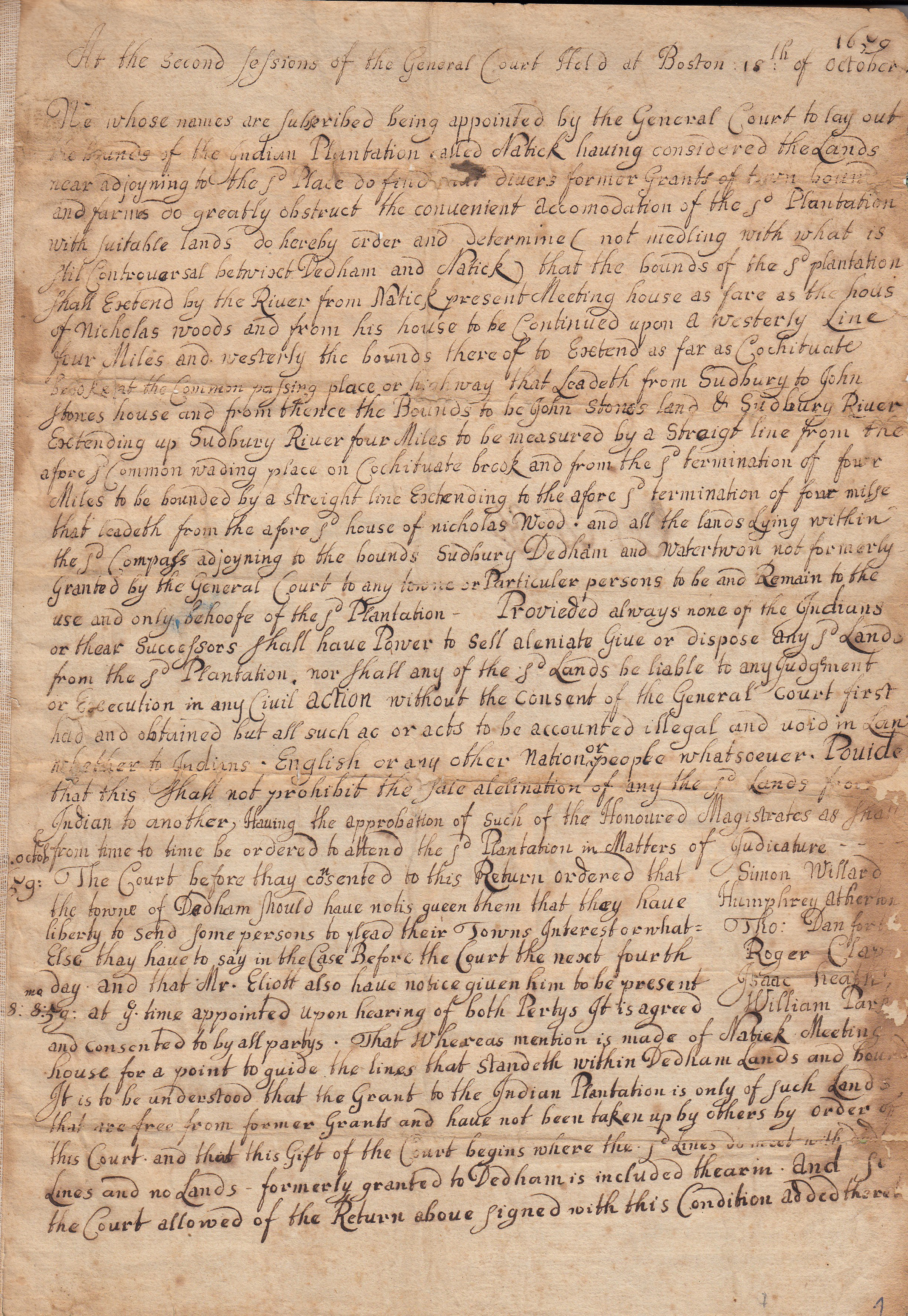

Had the Commission been consulted before construction began, we would have again warned the Board of Selectmen that previous ground radar surveys have indicated numerous colonial-era interments outside of the current Old Burial Ground (OBG) walls. Additionally, the wooded parcel that was cleared last week was also the most likely location of the original pre-contact Native American burial ground. Further soil disturbance so close to the OBG risks disinterment of human remains.

Equally critical, the clear-cutting of century-old woodland has now destroyed the windbreak for the trees in the Old Burial Ground, which were already in extremely precarious condition. With this protection removed, the OBG trees will now be highly susceptible to storm damage, which in turn risks the historic markers below.

Following the Historic Commission’s stated objection about felling trees on scenic roads, I have formally objected to the removal of any further trees on the site, in particular those along Marlborough Road.

Additionally, I would strongly advise the Board of Selectmen to work with the Historical Commission to fund an emergency professional tree survey of the Old Burial Ground with the idea of assessing the state of the remaining specimens, and doing any required pruning or removal before the onset of the winter storm season, in order to mitigate further damage to the burial stones. Long-term, there needs to be a proactive tree and marker restoration plan with sufficient annual funding to preserve the integrity of our most precious historical asset. There should also be a permanent marker acknowledging the Native American presence in this area.

Regarding the park itself, in my professional capacity as the head of a landscape architecture firm, I have reviewed the proposed planting plan and design, and found them extremely lacking. The plant selection is poor and makes no provision for climate change. Even more worrisome, the entire design was conceived around a central play area that has been eliminated, rendering the current layout useless.

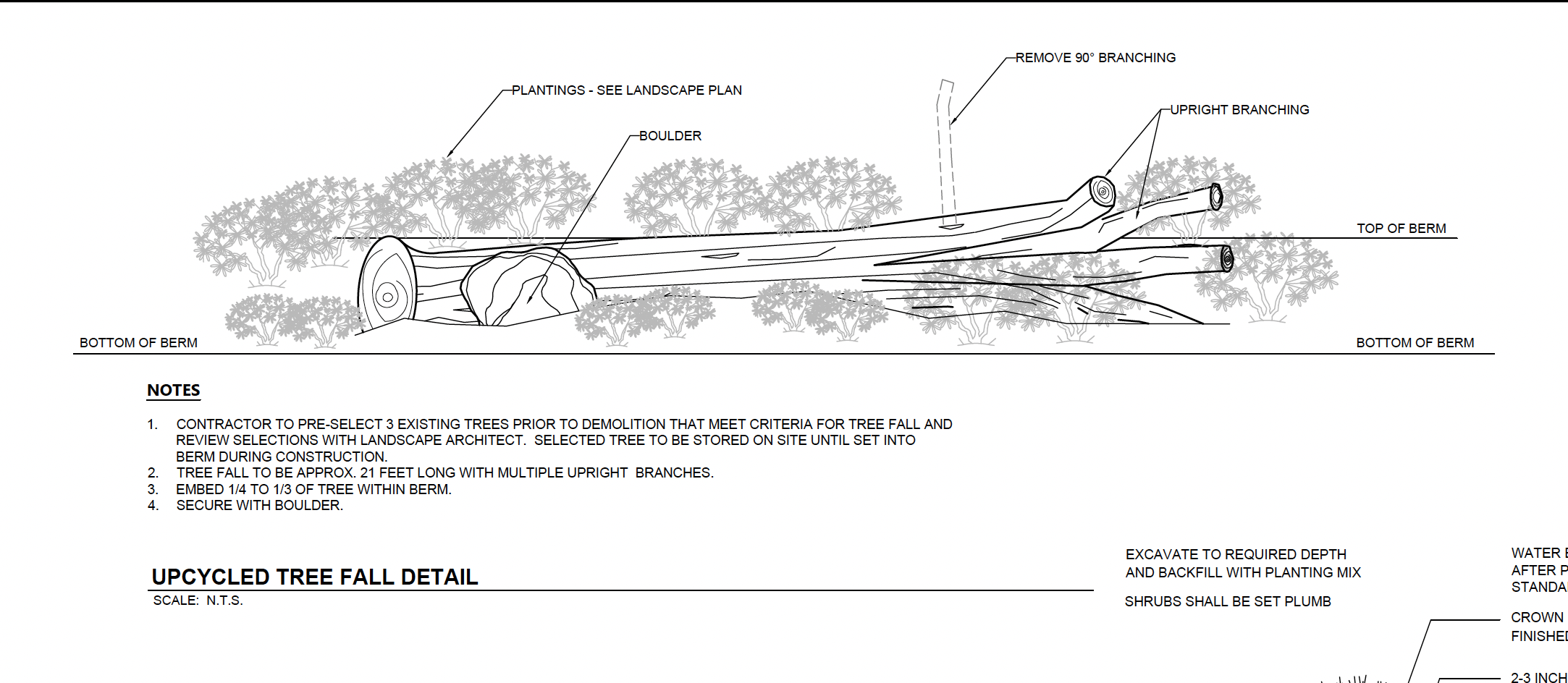

In particular, the proposal to cut down three large trees and use them sideways as some sort of tree-sculpture-berm-structure borders on the absurd, as after only a short period of ground contact, these trees will rot and create a huge legal liability for the town should anyone climb on them. There is also the issue of the historic stone wall along Marlborough road that will be destroyed if the current plans are implemented, violating our own preservation bylaw.

I would urge the Select Board to halt this project immediately until it can be thoroughly reviewed and approved by the Town Boards which should have been consulted before construction began: namely, Planning, Historical and Open Space. It remains unclear how much—if any—use by town residents the current “park” would have on such an isolated site without any attraction. The entire concept should be thoroughly reconsidered. Whatever else may happen to this parcel in the future, it is critical the area bordering the Old Burial Ground not be further disturbed, the expansion of the St. Mark’s parking area be visually mitigated, plans be made to restore the tree cover along the boundaries of the triangle, and immediate steps taken to preserve the existing trees and markers in the OBG.