Ladies and Gentlemen,

History waits for no weather.

Heritage Day is officially on! Come to the Museum tomorrow October 9 2017 at noon to see the 1868 Falcon fire engine do its stuff, plus view recent acquisitions.

The fun starts at noon!

Southborough Historical Society

Preserving Our Past for Your Future

More than a century ago, Southborough’s fires were fought by a handtub named the Falcon. A handtub is a hand pumped fire engine that shoots water over 200 feet — a major improvement over water tossed from a bucket! The Falcon was built in 1868, and purchased by the town of Southborough for $150 in 1896 after a series of deadly fires.

This coming Heritage Day, October 9th, residents will be able to see the Falcon in the parade, as well as watch a live demonstration — thanks to our firefighters — in front of the Southborough Historical Society Museum at noon. The Museum, which is half-way through its renewal process, will be open until 2, displaying its first two new exhibits in a decade: The Printed Word in Southborough: 1847 – the Present; and the 17th Century Sawin Family Papers

Michael Weishan, current President of the Society, is working with board members to expand the Society’s mission and promote the educational and cultural value of the museum’s collection. “We have one of the most spectacular collections in the area, and it’s high time we put it to work showcasing the almost 4000 years of habitation in the place we now call Southborough.”

The Society invites all residents to stop by and watch the Falcon demonstration and learn something new about our town.

Find out more about Southborough’s history at www.southboroughhistory.org.

At the Southborough Selectmen’s meeting last night it was announced that ca. 1810 Moses and Elizabeth H Fay House at 135 Deerfoot Road had been sold, and that the Town of Southborough had the right of first refusal to buy the property and its 35 acres under a program commonly known as 61A. The program gives a tax break to the owners of agricultural properties as long as they are kept in production. When the owner of a 61A property decides to sell, the municipality that has been granting the discounted tax rate is allowed first right of refusal. That time has now come for Southborough.

First, a little bit about the history of the house and land. The property, commonly called “Cedar Acres” for the large grove of pines located near the house, has been a farm since the early 1800’s, perhaps even the late 1700s, though its first recorded date is 1831. Three generations of Fays, one of Southborough’s founding families, farmed the property throughout the 1800’s. In the 1920s, the property was bought by Elgin John Rowe, an advertiser, as a gentleman’s farm. It is Rowe who updated the facade of the house in the Colonial Revival Style so popular in that era. Of the many original farm outbuildings, only the mid-19th century wooden gable front barn remains, a remarkable survivor of our agricultural past. (You can read the full historical report on the property HERE.)

Last night we learned that the property has been purchased by a developer, Brendon Homes, who builds perfectly nice and entirely banal developments all over New England in a style that has come to be derisively called “Contractor Palladian” on account of its many odd-shaped intersecting gables that violate traditional building proportions.

So let’s say, best case, the developer decides to preserve the historic structure on a tiny half acre or acre lot, and then do what they have done so many times in this area, which is to strand it among a sea of new single-family homes, the sole remaining testament to a once glorious agricultural past. Now my understanding from last night’s meeting is that some of the acreage may be wet and unbuildable, so for argument’s sake, let’s discount 15 acres, and presume 20 new homes on these 35 acres, each home costing $750,000. At our current assessment rate of $16.32 per thousand, that generates a tax return to the Town of Southborough of $12,240. If the houses go for a million dollars each, that amount would be $16,320; a million and half; $24, 480. You get the picture.

Now what does it cost the Town of Southborough for each one of these houses? Well, according to the State of Massachusetts, a typical 3-4 bedroom home will have 1.9 school-age children in residence throughout the life of the home. Here in Southborough, we spend $17,763.41 per student, per year.

So if you do some simple math, it costs the Town $33,750.47 per year for those 1.9 students. This price tag does not include new buildings to accommodate more students, nor does it budget for the cost of increased fire, police or public service costs. The simple fact is that every new house built on this land will take money out of your wallet, my wallet, and the wallet of every other resident in Southborough, FOREVER, because you and I pay the difference between income and outlay. The developer builds, takes the profits, leaves town, and leaves US to foot the bill.

So what’s our recourse? Simple: the Town should exercise its right and buy the property for $1.9 million. That would cost us something as well, but with 20 homes costing us 34K or more a year (675K total per annum) the pay-back period is 2.8 years. That’s right folks. 2.8 years! After that, it’s 675K in savings per year, forever. Obviously the pay-back period changes depending on the cost of the home; it could be longer, it could be shorter — far shorter if some sort of massive cluster development is planned that floods our schools with new residents like the planned Park Central, which is a distinct possibility. By almost under any scenario, we win by exercising our 61A rights.

What would the Town do with the property? The simplest answer would be open space protection — this particular parcel has been flagged since at least the late 1990’s as critical wildlife habitat. (The house with 1 or 2 acres could be separated and sold as a private residence to recoup part of the cost.) Another option would be to use a small piece of the property (keeping the remainder as open space) to create affordable housing, something sorely lacking in Southborough. If there is no appetite for that, a further option would be to simply buy the property, place a conservation restriction on the land and a preservation restriction on the historic structures, and put the property back on the open market. The resale value would be less than the acquisition cost, but again we would gain that money back almost immediately by preventing development.

The morale of the story here for Southborough, in fact, for any community in Massachusetts, is that our open space is more valuable to us when open, for host of reasons. This particular parcel even more so, as it is one of the last intact gentleman’s farms from an era when Southborough was a center for agricultural pursuits. (Southborough was, in fact, the second most productive agricultural town in Massachusetts.) Let’s hope common sense prevails here, and we acquire this property within the 120 day window allowed by the 61A law. It’s a win for historic preservation, it’s a win for wildlife habitat and open space, it’s a win for the preserving the quality of life in Southborough, and most importantly, it’s a win for our wallets.

9/20/17: Editor’s Note: Due to an unintentional misstatement by one of the speakers at the Selectmen’s meeting, the Moses and Elizabeth Fay House property was described as 35 acres – 27 on the west side of Deerfoot Road, and 7 across, which we duly relayed. However, we were informed today by a member of the Open Space Committee that the actual figure is 20 acres on the west side, and 7 acres across the road, which has been verified by plot plan. Additionally, the wetland area seems far less than predicted, so increased development may be possible. For editorial integrity, I have not altered the original post.

Working with a collection as rich and diverse as the Society’s has constant rewards. Take this letter for instance, written to Susie R. Ingalls, of Cambridge Massachusetts, by her daughter Mabel. It records an idyllic May Day long ago, in an age long past.

Southborough May 1, 1897

My dear Mamma

We arrived here Friday morning as half past eight after a very tiresome night. The boat arrived at New London at twelve o’clock but the train did not go until five minutes after four — arriving at Worcester at 6:55. We had no trouble at all changing cars as someone would show us right to the car even offering to carry our bundles. I like it here very much. Mr. Burnett’s house is very much after the style of Mr. Beecher’s house at Peekskill. Auntie was very excited when we came, rushing to the door and losing her cap as I have often heard you tell of. Friday afternoon I went for a drive with Mary and Charlie Jimmerson and we were caught in a heavy thunder shower and the horse was afraid so we drove into a barn and stayed about an hour; we had a box of candy and had a real nice time. Mary’s father has given them a row boat which was a great surprise so we thought that would be an idea for a name, so it will be named “The Surprise.” We are going out in it every day and yesterday I tried rowing. Saturday afternoon Susie Sawin and her cousin George came; you certainly would not take him for a teacher. He is an awful one to carry on — he plagues Auntie so gets she real angry in a good-natured way. He put the clock back and it got into about the shape our back parlor clock used to be and [he] did not get up until we were all through breakfast, so we put cayenne pepper in his oysters and coffee. Susie and Mary are both splendid, and so is Cousin Charlie’s wife; she looks young, not much over thirty, and goes around rowing and makes it just as pleasant as she can for everyone and she does not do any work except cooking; she calls Auntie “mother” and they all just love her. Last night we all went to an entertainment at the town hall. It was singers and a short play in which Mary was ‘Bridget’ and Mrs. Sawin took part. This is an awful place for clothes — the dog will run to meet us and jump up and get his dirty paws all over you. Alice stays at the mill all day and goes to ride with Harry a great deal. The Burnett’s were expecting the Vanderbilts but we did not see them come. Alice, Harry, Susie, Mary and I have just come home from church. George stayed home to shave. Alice and I sleep together in the front room. Mrs. Sawin is going to show us her room and all the things she got as presents. Auntie say she will be terribly disappointed if you do not come up and that we have to got to make a long visit at Riverside. She is going to give Alice money for a canary bird, and Susie Sawin has got a pair of shoes 4 1/2 and she wears a 5 so I guess that Auntie will send them to you. I guess I most close now as the table is set for dinner. So goodbye with much love to all, your loving daughter, Mabel

PS We are going to hang George a May basket tonight.

There are so many fascinating hints and clues about the times in this letter! The reference to taking the boat to New London, for instance, recalls an age when it was easier and far more comfortable to get to central Massachusetts from New York City by taking the night ferry than by taking the hodgepodge of competing rail lines. (The famed Boston consist of the 20th Century Limited wouldn’t arrive until 1902, for example.) And where precisely is Mabel staying? Obviously at one of the Burnett Houses, but which — the Burnett Mansion, or Edward Burnett’s house across Stony Brook? That would tell us who Auntie is.

And then there is that fascinating reference to “Mr. Beecher’s House in Peekskill.” It turns out Henry Ward Beecher, the famous abolitionist, had a summer house in Peekskill, New York, which was a famous stop on the underground railroad. The house, which was described in a 2001 New York Times article when the building was proposed for a museum, still exists, though the museum project never went forward. Take a look for yourself: it does rather look like a mini- Burnett mansion.

(NOTE 9.21/17 One of our board members, Deborah Costine, pointed out this probably wasn’t the house Mabel was referring too, but rather THIS ONE which makes more sense, due to its country setting and resemblance to the now destroyed Edward Burnett House.)

The Sawin’s are now more of a known quantity, of course, since our recent discovery of their historic family documents. But oysters for breakfast? It seems so: check out this recipe for Oysters a la Thorndike, listed in the 1896 edition of the Boston Cooking School Cookbook.

All in all, Mabel’s letter is wonderful reminder of an age long lost, when Southborough was not only a bucolic farming community, but also a summer retreat of the New York and Boston elite.

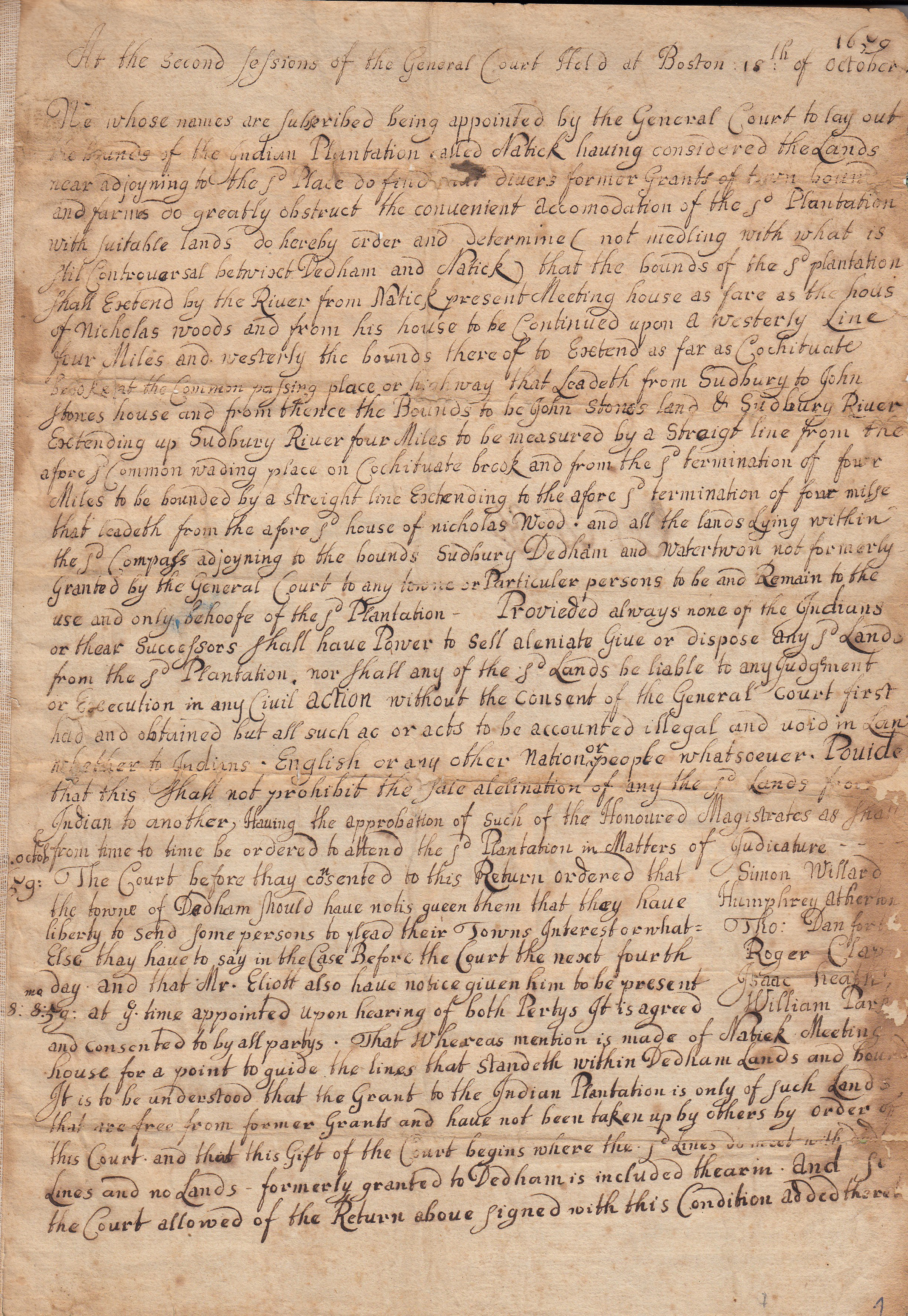

The Southborough Historical Society is absolutely thrilled to announce the discovery of 13 exceedingly rare early 17th-century documents relating to the Sawin family of Southborough. The items record, among other matters, the 1656 layout of the village of Praying Indians at Natick, the 1686 sale of 5 acres of land there for the construction of a mill by Thomas Sawin, and subsequent grants and transactions. These documents are critically important to our local area history, as they detail the early interactions between the newly arrived settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the native peoples of this region, the Nipmuc tribe. The Nipmuc, almost entirely forgotten today, had lived throughout central Massachusetts for thousands of years, including sites in Southborough. In fact, the basic layout of Southborough along the lines of Route 30 and Cordaville Road follows the fishing and hunting trails, farming fields and camps sites established by the Nipmuc people many centuries ago.

The Nipmuc initially welcomed the English to the area, believing there was “enough land for all.” However, tensions rose quickly, as English settlers began proselytize the natives, as well as impose their rigid system of land division on the formerly nomadic tribe. The English held the view that any “empty” land could be assigned to specific owners and enclosed for cattle and other grazing animals, while the itinerant Nipmuc felt that the land must remain open for the common good. Add to the mix the Europeans’ introduction of firearms and alcohol to the native peoples, and an already difficult situation became highly volatile. Our 1656 document is witness to this growing conflict, as it defines the borders of the Natick Village of “Praying Indians”— members of the Nipmuc tribe who had adopted Christianity and European ways — while conveniently and simultaneously opening up surrounding areas for English settlement. Eventually there were a dozen or so of these Praying Indian villages, including at Marlborough, which led directly to the founding of Southborough. Needless to say, this quasi-coerced religious conversion and assignment to specific “villages” (which the white peoples would later term “reservations”) was resented by the majority of Nipmuc who remained faithful to their traditional ways. The inevitable conflict came in 1675, when the Nipmuc and their allies rose up against the English. The subsequent bloody conflict, essentially a battle fought to determine supremacy between two conflicting cultures, came to be called King Phillips War and marks the birth of one nation, and the death of another.

For the English, who were fighting for their vision of a Christianized New World, the war meant the loss of 1 out of every 10 military age men; 1000 civilian casualties; the complete destruction of 12 of the region’s towns; attacks on half the others; (including Marlborough and Sudbury) and damage to farms, mills and other property sufficient to set the colony’s economy back two decades. Fought entirely without English aid, King Philip’s War also marked the beginning of an American identity separate to that of Europe.

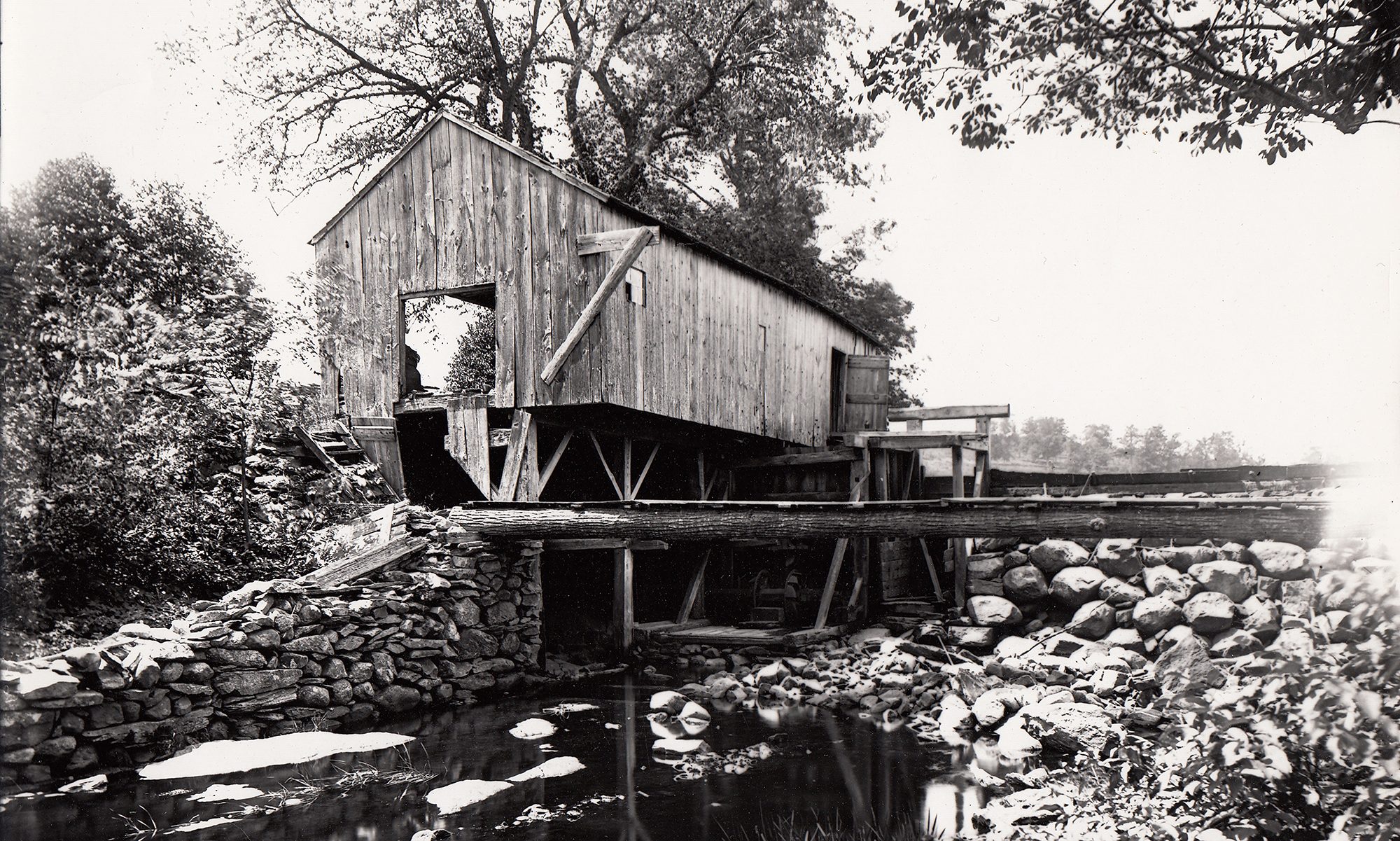

For the Nipmuc and their regional allies, it meant not only the extermination of their way of life, but their virtual extinction. Those who didn’t flee were slaughtered by the thousands, and at the end of the conflict the remaining native survivors of the area were rounded up by the English — including the Christianized Indians of Natick and the other Praying Towns — and interned on Deer Island in Boston Harbor where they were left to die of starvation and disease. Hundreds of others were sold into slavery. Eventually, a small number returned to their former homes to live under English rule, but the viability of their culture had been destroyed. Our 1685 document, the Thomas Sawin deed, is an extremely rare survivor of this postwar period, and gives a rare glimpse of what life was like at Natick ten years after King Phillip’s War. The diminished Nipmuc, who had since become accustomed to eating ground corn, were desirous of a mill in their village. So they invited Thomas Sawin, who had already built a mill at Sherbourne, to come live among them and set up a mill. Their offer was 50 acres of land on the stipulation that he and his heirs and assigns were to maintain the mill forever, and that there was to be no other corn-mill built in town without the consent of Thomas Sawin, his heirs and assigns. Thomas Sawin kept his word, built the mill, and lived peaceably among the natives for the rest of his life, but even more importantly, he became an advocate for native rights at the Massachusetts General Court. This progressive stance would remain the hallmark of the Sawin family, as we shall see.

So how did these remarkable documents wind up in Southborough? Well, long story short, the answer was the response to another epic battle in American history, the fight against slavery. Fast forward 148 years to 1833 where Moses Sawin is still running his grandfather Thomas’ mill at Natick:

To quote the 1876 History of Southborough by Dexter Newton:

“When the clarion notes of William Lloyd Garrison rang through the land calling the nation to repentance for supporting and maintaining chattel slavery, Mr. Moses Sawin did not hesitate to enlist in the great cause of humanity. He was convinced it was a sin against God and a crime against his brother man.

He had the courage to ask the members of the church to which he belonged to testify against the sin; when his request was rejected he refused to commune with them as a church of Christ, and when, for this refusal, they cast him out of the church, he exultantly quoted to them the words of Christ, viz.: “Inasmuch as ye did it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye did it unto me.” He was especially gratified that he had lived to see slavery entirely abolished; it was what he had long labored for and sought. But the crowning glory of his latter days was in hearing his former opponents acknowledge the righteousness of his cause, and labor earnestly with him in the overthrow of American slavery.”

So translated to the modern vernacular: Moses Sawin became such an vocal abolitionist that when his fellow Natick church members tired of him and tossed him out, he picked up stakes and moved to Southborough. As Newton relates:

Moses Sawin purchased the grist and saw-mill and a small lot of land situate one-half mile west of Town Hall, in Southborough, of Deacon Gabriel Parker, in 1833. The year following he bought of said Parker seven acres of land adjoining same, and on south side of Mill Pond, and built thereon a spacious dwelling-house, barn and other buildings. The estate is now owned and occupied by Charles B. Sawin, youngest of his three surviving sons. (The sawmill and house are long gone, but were located just south of the MDC damn on Deerfoot Road, which in many ways mimics the Sawin damn and mill pond of old.)

And then comes the kicker:

Said Moses Sawin possessed and carefully preserved through life the curious old deed, signed and sealed by the Indian chiefs of whom his said ancestor purchased the land. They are now in possession of said C. B. Sawin, at the old home-stead, where antiquarians and others interested in curious legal documents can examine them.

And thus, our amazing trove of documents!

The Sawin family remained active in Southborough right up until the 1960s, owning the still extant brick building on Boston Road, now home to Falconi Oil, which was once their feed store. They owned too a large house at 10 Latisquama Road. It seems that when the last Sawin descendants left Southborough sometime in the 70s, they donated their precious family papers to the Southborough Historical Society. The various documents had by then been bound into an innocuous leather volume appropriately labeled Sawin Family Documents, but without any text or explanation. As such, it was dutifully placed on a basement storage shelf, and promptly forgotten. Then came the 2015 flood, and these priceless documents narrowly missed inundation. Returned to the Museum from temporary storage this spring, it wasn’t until we began the arduous process of unpacking, rehousing and cataloguing the material did we discover the true value of what had been sitting on our shelves for 50 years. Today, the 13 documents have been carefully removed from their leather binding, which was showing signs of mold, carefully rehoused in archival envelopes, and stored in our new climate-controlled safe.

So what’s next? Well, first of all we will digitize these documents and share them with the world. We’ve already been in touch George Sawin, who leads the Sawin Family Association, who’s come to see documents at the Museum, and who, coincidentally, is spearheading the preservation of Thomas Sawin’s endangered 18th century homestead, which still graces the banks of the Charles River at Natick. Next, partially based on this amazing trove, we’ve applied for funding for a new traveling exhibit, “The Nipmuc, the English, and New England’s First Forgotten War” which will debut at the museum in the fall of 2018 and then travel to local area schools and institutions.

The importance of this find can’t be understated. The documents are of Smithsonian-level quality and importance, incredibly rare paper survivors from the earliest days of our nation. We are honored to be their conservators — which we can only do with your continued help and generous support.

Dear History Friends,

I was working today at the Museum with our wonderful senior assistant, Donna McDaniel, in the extended process of getting our photographic and paper collections organized. Donna (our first woman Selectman back in the day) had left about 20 minutes earlier for one of her two additional engagements in Worcester and Sudbury (in one day, and this lady remembers FDR!!, wow!) when suddenly a storm came up, the skies darkened, and it rained a summer-storm white-out. It was really something: fierce, yet all water. When I looked out the window at the passing, this is what I saw:

How often do you see a rainbow over the Old Burial Ground, where not only our first European settlers, but also our Native American fore-bearers, the Nipmuc Tribe, are buried? Or for that matter, how often do you see a rainbow on the ground, period? In my 52-odd years, this is a first. Unfortunately, Donna, a long time reporter, was not here to witness this event and confirm the viewing, but I assure you this is a real photo, and hopefully a sign of heavenly approbation for our continuing efforts at preserving Southborough’s centuries-old history.

I often think as I get in my car to travel the three or four minutes from my home to the museum, how long this trip would have taken a hundred years ago. Granted, I might have had a car in 1917, but more likely for Southborough, I would have had a horse, and saddling a horse and riding those few miles is a half-hour operation at best. Walking is about the same (you save the time of saddling and unsaddling) and biking was (and is) about 10 minutes, with one major hill.

Imagine then how thrilling it must have been to go from Boston to Worcester in 2 hours by trolley! Now of course, train travel had been around since the 1830s, but with limited local service. The Boston & Albany’s tracks on the border with Hopkinton were a major freight line, as well the route of the named ‘varnish’ trains (the Boston end of the famed 20th Century Limited passed daily through Southborough, for instance) headed for New York, Chicago and all points west.

But on a trolley, all things were local. You could get on and off at will, plus, during the summer months the cars were open-air, and the route truly scenic. Speaking of the Southborough portion west to Worcester, the booklet below simply glows: “This portion of the road, running through woods and fields, with fleeting glimpses of all that makes the New England landscape famous, give the tourist a trip long to be remembered.” To the east of Southborough the route ran through the middle of today’s Rt 9, the old Boston Worcester turnpike, which by the time of the Airline’s construction in 1901, had been largely abandoned. It must have been an incredibly beautiful trip through the rolling hills of unspoiled countryside and quaint little villages, and in fact the Airline ran special cars for “Trolley Parties,” which were popular day-long excursions in the early 1900s.

The booklet below has never to my knowledge been published online, and is here represented in full size: just click on the images to expand. The very rare fold-out birds-eye view map is truly one-of-a-kind. The booklet is not dated, but can be reasonably assigned to the very first years of the Airline, as the map doesn’t show the White City Amusement Park, which became a major attraction on Lake Quinsigamond by 1905.

This first-time publication is the product of the Society’s continuing efforts to share our history widely and make our collections accessible to all, and a perfect example of why we need and value your continued financial support. Donations are easy to make online: just click the button at the end of this post. More pictures of the Airline are available HERE.

In the meantime, enjoy this long-lost booklet, newly restored to view.

Click on any image below to expand

The fold-out map below is 30″ long and 24MB. But, you can browse to your heart’s content. Maximize your browser size to fully enjoy!

Recently rediscovered in our photographic collection: Fourth of July, 1902 in Southborough with Ruth Ladd, Marguerite Henderson, Veda Henderson, Alice Hammond, the aptly named Rose Liberty, Evelyn Henderson, James E Griffin, and Corrina Liberty. The dog’s name is lost to history, but for today he can be ‘Firecracker.’

Recently rediscovered in our photographic collection: Fourth of July, 1902 in Southborough with Ruth Ladd, Marguerite Henderson, Veda Henderson, Alice Hammond, the aptly named Rose Liberty, Evelyn Henderson, James E Griffin, and Corrina Liberty. The dog’s name is lost to history, but for today he can be ‘Firecracker.’

Happy Fourth of July from all your friends at the Southborough Historical Society!

Ever wonder why Southborough lacks an historic railroad station, especially given the beauties that still exist in Framingham, Ashland, Westborough, and many other points along the old Boston and Albany line?

Well, in fact, we once had not one, but three!

The first, on the branch Agricultural Line to Marlborough, stood on Main Street, in the empty lot west of Lamy’s insurance:

It’s unclear what happened to this beautiful Queen Anne Structure after service was discontinued in the early 30s. Perhaps some of our older members might remember when this building was demolished? How we could use this building now as part of a revitalized main street! Wouldn’t it have made a fantastic pub?

It’s unclear what happened to this beautiful Queen Anne Structure after service was discontinued in the early 30s. Perhaps some of our older members might remember when this building was demolished? How we could use this building now as part of a revitalized main street! Wouldn’t it have made a fantastic pub?

My understanding was that Southville Station, seen below in its prime, was abandoned, vandalized and eventually demolished in the early 70s, the low-point of historical preservation in Southborough.

However, its near twin Cordaville Station had a different fate. I had heard tell that it had been moved to New Hampshire, but I was never able to confirm that.

Until now! Sorting through our files as we move back into our museum quarters, I discovered this remarkable clipping. Ho ho! A clue!

So now, do you suppose our once glorious station still exists somewhere in Dublin New Hampshire? I’ve contacted the Historical Society there, and hopefully we’ll soon find out.

So now, do you suppose our once glorious station still exists somewhere in Dublin New Hampshire? I’ve contacted the Historical Society there, and hopefully we’ll soon find out.

Regardless, the sad lesson to be learned here is that if you don’t value your historical structures, there’s always someone else that does…. much to the detriment of your own surroundings.

Moving forward, we need to guard our historic heritage much more actively, Southborough friends!

Dear Friends,

Thanks to your financial support over the last year, we have been able to make many strides in bringing materials previously locked away in the archives online for public viewing. Here are just some of the most recent offerings:

A Slide Tour of the Old Burial Ground

Join the late historian Kay Allen as she takes you through highlights of one of our most important historical treasures.

Historic Homes Database

Get information on the history of your home without leaving your desk!

Holy Hill Walking Tour

Grab the kids and take a fun and informative walking tour around the Museum with this out-of-print guide.

Southborough Historical Photos Collection

Take a look at our ever expanding collection of online photos.

Southborough Genealogical Resources

New means to research your families history.

Of course, we rely on you to help us make this happen. We have a number of volunteer positions open at the Society, and are always in need of ongoing financial support, so please keep those donations coming!