Recently I set myself the task of rehousing and cataloging the Francis B. Fay papers in our collection. I’ll be telling you more about these documents another time, as Francis B. Fay was one of Southborough’s more remarkable native sons, who among other notable deeds donated the money to start our library, which for many decades bore his name. But, I digress… back to the papers.

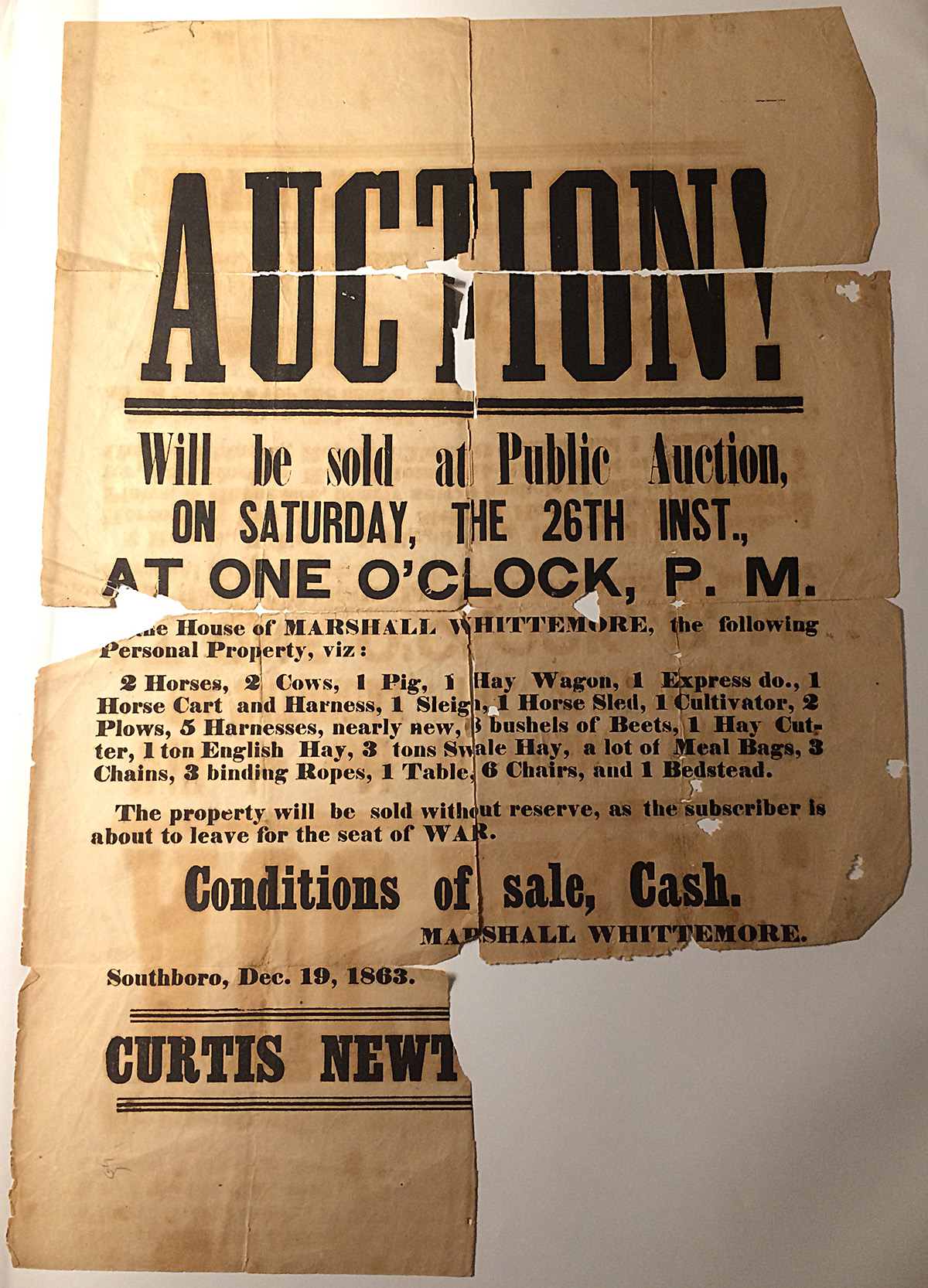

Cataloguing is not exactly a mile-a-minute roller-coaster ride of fun. It can be tedious, because there is a lot of minutia involved, but it’s critical if we really intend to take effective stewardship of our Southborough history. Most of the Fay papers were pamphlets of one type or another — very early sermons (some dating back to 1820), political tracts, speeches, and various other bits and pieces saved during a productive life of public service spanning 7 decades. But tucked away in one of these pamphlets, carefully folded up but literally rotting away with age, was the auction notice you see above. These broadsheets were never intended to be preserved; they were printed on the cheapest of paper, and generally thrown away afterwards. But somehow this one survived, and despite its damaged state, caught my attention because of the line below “CONDITIONS OF SALE”:

“The property will be sold without reserve as the subscriber is about to leave for the seat of WAR.”

“The seat of WAR” Wow!

It’s not everyday you find a notice of someone auctioning their possessions in order to go fight in the Civil War. There are so many questions here. We know from the historical record that Marshall Whittemore lived on the corner of Boston Road and Framingham Road, in a Greek Revival cottage that is remarkably little changed. We know too he was married with children, and his profession was listed as farmer. So why was he selling his animals and farm equipment? To make provision for his family? How were they going to live while he was gone? What motivated him to enlist in the first place? He was not at all young — 41 — and the war had been raging for over two years. Something, though, prompted him to sell his precious goods the day after Christmas, and shortly thereafter, leave his home, wife, son, and daughter to fight for the Union.

Can you imagine how difficult that parting must have been? Heading off in a cold, dark December to god-knows-what fate?

Fortunately, thanks to other records in our collection, we know that our story has a happy ending. Marshall Whittemore, now a private in a heavy artillery regiment, survived the disastrous battle of Newport Barracks where Union troops were overwhelmed 3-1 by Confederate forces. At the conclusion of hostilities, he was mustered out of the Army, returning to farm and family in Southborough where he lived peaceably for decades. He died in 1902 and is buried in the Rural Cemetery.

So the historical record is all neatly tucked up, but it leads to a final nagging question: why did Francis B. Fay decide to save this seemingly random broadsheet? Were the two men friends? Friends of friends? Distantly related? Or did Francis Fay simply admire the courage of a man who sold his most precious possessions, left his family, and headed off to war with the courage of his convictions. We’ll never know, but it’s something to remember as we fuss with ribbons and wrappings, fret over last-minute shopping, fume over holiday traffic, and worry endlessly about menus and decorations, that once upon a time, in a Southborough long, long ago, a certain courageous man named Marshall Whittemore gave up his home and hearth at Christmas, so that we of future generations could enjoy ours.

Thank you, Marshall. Thank you indeed.

And Merry Christmas.