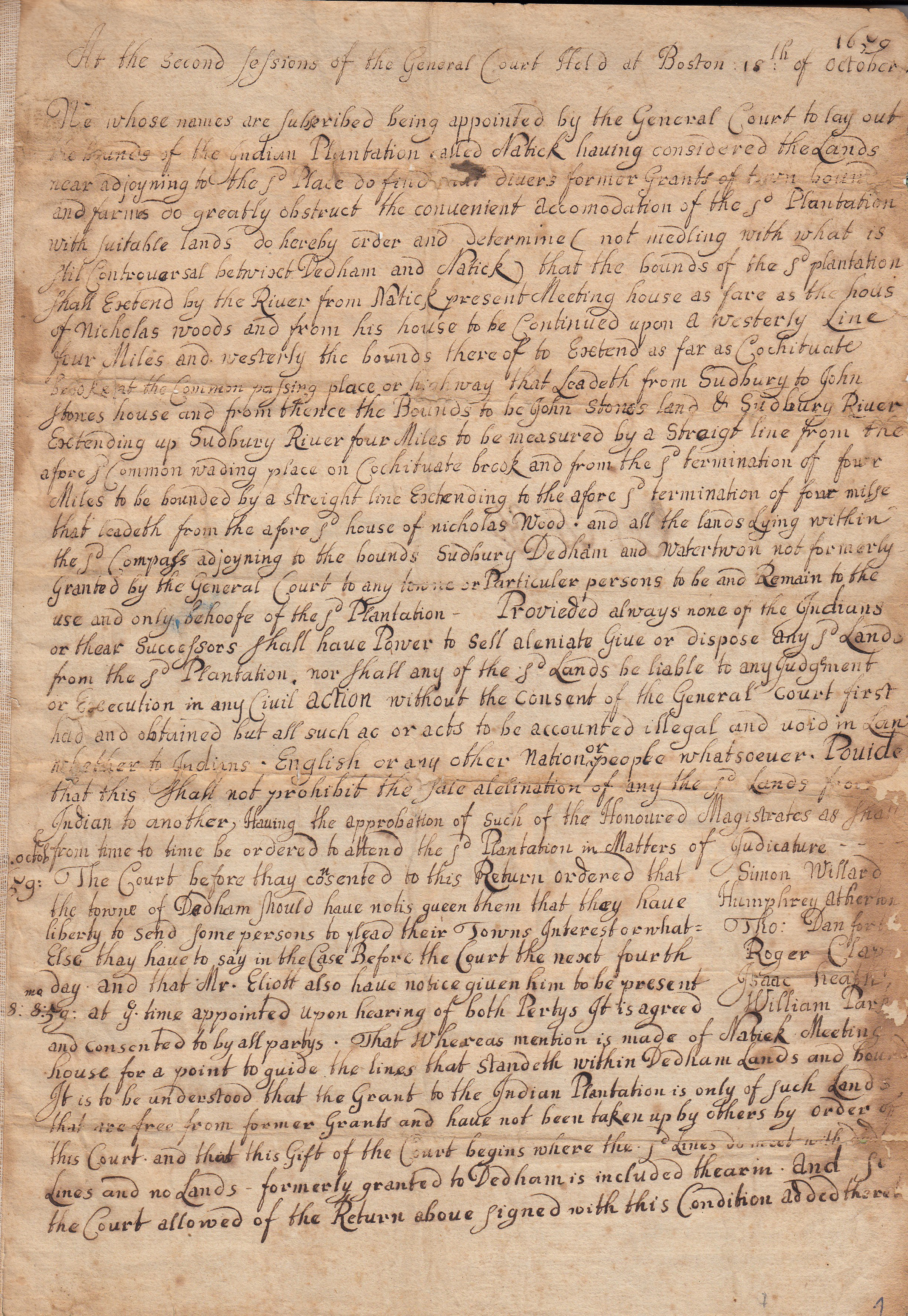

The Southborough Historical Society is absolutely thrilled to announce the discovery of 13 exceedingly rare early 17th-century documents relating to the Sawin family of Southborough. The items record, among other matters, the 1656 layout of the village of Praying Indians at Natick, the 1686 sale of 5 acres of land there for the construction of a mill by Thomas Sawin, and subsequent grants and transactions. These documents are critically important to our local area history, as they detail the early interactions between the newly arrived settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the native peoples of this region, the Nipmuc tribe. The Nipmuc, almost entirely forgotten today, had lived throughout central Massachusetts for thousands of years, including sites in Southborough. In fact, the basic layout of Southborough along the lines of Route 30 and Cordaville Road follows the fishing and hunting trails, farming fields and camps sites established by the Nipmuc people many centuries ago.

The Nipmuc initially welcomed the English to the area, believing there was “enough land for all.” However, tensions rose quickly, as English settlers began proselytize the natives, as well as impose their rigid system of land division on the formerly nomadic tribe. The English held the view that any “empty” land could be assigned to specific owners and enclosed for cattle and other grazing animals, while the itinerant Nipmuc felt that the land must remain open for the common good. Add to the mix the Europeans’ introduction of firearms and alcohol to the native peoples, and an already difficult situation became highly volatile. Our 1656 document is witness to this growing conflict, as it defines the borders of the Natick Village of “Praying Indians”— members of the Nipmuc tribe who had adopted Christianity and European ways — while conveniently and simultaneously opening up surrounding areas for English settlement. Eventually there were a dozen or so of these Praying Indian villages, including at Marlborough, which led directly to the founding of Southborough. Needless to say, this quasi-coerced religious conversion and assignment to specific “villages” (which the white peoples would later term “reservations”) was resented by the majority of Nipmuc who remained faithful to their traditional ways. The inevitable conflict came in 1675, when the Nipmuc and their allies rose up against the English. The subsequent bloody conflict, essentially a battle fought to determine supremacy between two conflicting cultures, came to be called King Phillips War and marks the birth of one nation, and the death of another.

For the English, who were fighting for their vision of a Christianized New World, the war meant the loss of 1 out of every 10 military age men; 1000 civilian casualties; the complete destruction of 12 of the region’s towns; attacks on half the others; (including Marlborough and Sudbury) and damage to farms, mills and other property sufficient to set the colony’s economy back two decades. Fought entirely without English aid, King Philip’s War also marked the beginning of an American identity separate to that of Europe.

The 1685 deed to Thomas Sawin, sealed and signed by the four elders of the Natick Village.

For the Nipmuc and their regional allies, it meant not only the extermination of their way of life, but their virtual extinction. Those who didn’t flee were slaughtered by the thousands, and at the end of the conflict the remaining native survivors of the area were rounded up by the English — including the Christianized Indians of Natick and the other Praying Towns — and interned on Deer Island in Boston Harbor where they were left to die of starvation and disease. Hundreds of others were sold into slavery. Eventually, a small number returned to their former homes to live under English rule, but the viability of their culture had been destroyed. Our 1685 document, the Thomas Sawin deed, is an extremely rare survivor of this postwar period, and gives a rare glimpse of what life was like at Natick ten years after King Phillip’s War. The diminished Nipmuc, who had since become accustomed to eating ground corn, were desirous of a mill in their village. So they invited Thomas Sawin, who had already built a mill at Sherbourne, to come live among them and set up a mill. Their offer was 50 acres of land on the stipulation that he and his heirs and assigns were to maintain the mill forever, and that there was to be no other corn-mill built in town without the consent of Thomas Sawin, his heirs and assigns. Thomas Sawin kept his word, built the mill, and lived peaceably among the natives for the rest of his life, but even more importantly, he became an advocate for native rights at the Massachusetts General Court. This progressive stance would remain the hallmark of the Sawin family, as we shall see.

So how did these remarkable documents wind up in Southborough? Well, long story short, the answer was the response to another epic battle in American history, the fight against slavery. Fast forward 148 years to 1833 where Moses Sawin is still running his grandfather Thomas’ mill at Natick:

To quote the 1876 History of Southborough by Dexter Newton:

“When the clarion notes of William Lloyd Garrison rang through the land calling the nation to repentance for supporting and maintaining chattel slavery, Mr. Moses Sawin did not hesitate to enlist in the great cause of humanity. He was convinced it was a sin against God and a crime against his brother man.

He had the courage to ask the members of the church to which he belonged to testify against the sin; when his request was rejected he refused to commune with them as a church of Christ, and when, for this refusal, they cast him out of the church, he exultantly quoted to them the words of Christ, viz.: “Inasmuch as ye did it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye did it unto me.” He was especially gratified that he had lived to see slavery entirely abolished; it was what he had long labored for and sought. But the crowning glory of his latter days was in hearing his former opponents acknowledge the righteousness of his cause, and labor earnestly with him in the overthrow of American slavery.”

So translated to the modern vernacular: Moses Sawin became such an vocal abolitionist that when his fellow Natick church members tired of him and tossed him out, he picked up stakes and moved to Southborough. As Newton relates:

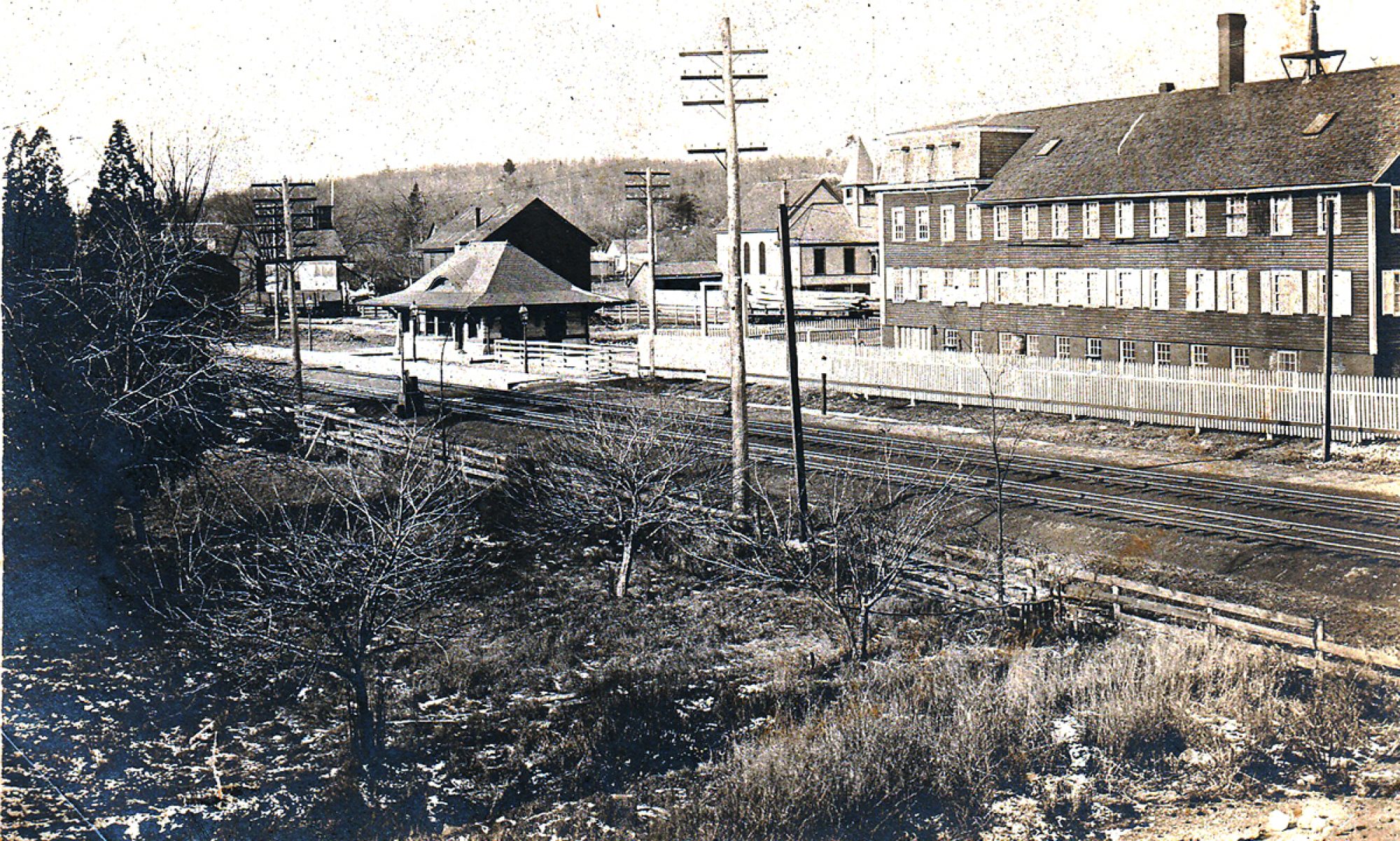

Moses Sawin purchased the grist and saw-mill and a small lot of land situate one-half mile west of Town Hall, in Southborough, of Deacon Gabriel Parker, in 1833. The year following he bought of said Parker seven acres of land adjoining same, and on south side of Mill Pond, and built thereon a spacious dwelling-house, barn and other buildings. The estate is now owned and occupied by Charles B. Sawin, youngest of his three surviving sons. (The sawmill and house are long gone, but were located just south of the MDC damn on Deerfoot Road, which in many ways mimics the Sawin damn and mill pond of old.)

And then comes the kicker:

Said Moses Sawin possessed and carefully preserved through life the curious old deed, signed and sealed by the Indian chiefs of whom his said ancestor purchased the land. They are now in possession of said C. B. Sawin, at the old home-stead, where antiquarians and others interested in curious legal documents can examine them.

And thus, our amazing trove of documents!

The Sawin family remained active in Southborough right up until the 1960s, owning the still extant brick building on Boston Road, now home to Falconi Oil, which was once their feed store. They owned too a large house at 10 Latisquama Road. It seems that when the last Sawin descendants left Southborough sometime in the 70s, they donated their precious family papers to the Southborough Historical Society. The various documents had by then been bound into an innocuous leather volume appropriately labeled Sawin Family Documents, but without any text or explanation. As such, it was dutifully placed on a basement storage shelf, and promptly forgotten. Then came the 2015 flood, and these priceless documents narrowly missed inundation. Returned to the Museum from temporary storage this spring, it wasn’t until we began the arduous process of unpacking, rehousing and cataloguing the material did we discover the true value of what had been sitting on our shelves for 50 years. Today, the 13 documents have been carefully removed from their leather binding, which was showing signs of mold, carefully rehoused in archival envelopes, and stored in our new climate-controlled safe.

So what’s next? Well, first of all we will digitize these documents and share them with the world. We’ve already been in touch George Sawin, who leads the Sawin Family Association, who’s come to see documents at the Museum, and who, coincidentally, is spearheading the preservation of Thomas Sawin’s endangered 18th century homestead, which still graces the banks of the Charles River at Natick. Next, partially based on this amazing trove, we’ve applied for funding for a new traveling exhibit, “The Nipmuc, the English, and New England’s First Forgotten War” which will debut at the museum in the fall of 2018 and then travel to local area schools and institutions.

The importance of this find can’t be understated. The documents are of Smithsonian-level quality and importance, incredibly rare paper survivors from the earliest days of our nation. We are honored to be their conservators — which we can only do with your continued help and generous support.

Your donations make discoveries like this possible. Please help support the Southborough Historical Society!