Continuing our publication of Col. Francis Fay’s letters, I thought any of you with the experience of young charges might delight in knowing that things haven’t changed much in 170 years. Here, our hero writes to his two sons, Frank and Henry, explaining why he’ll never buy an I-Phone 11 (or the 1850s equivalent)—for himself, or for them.

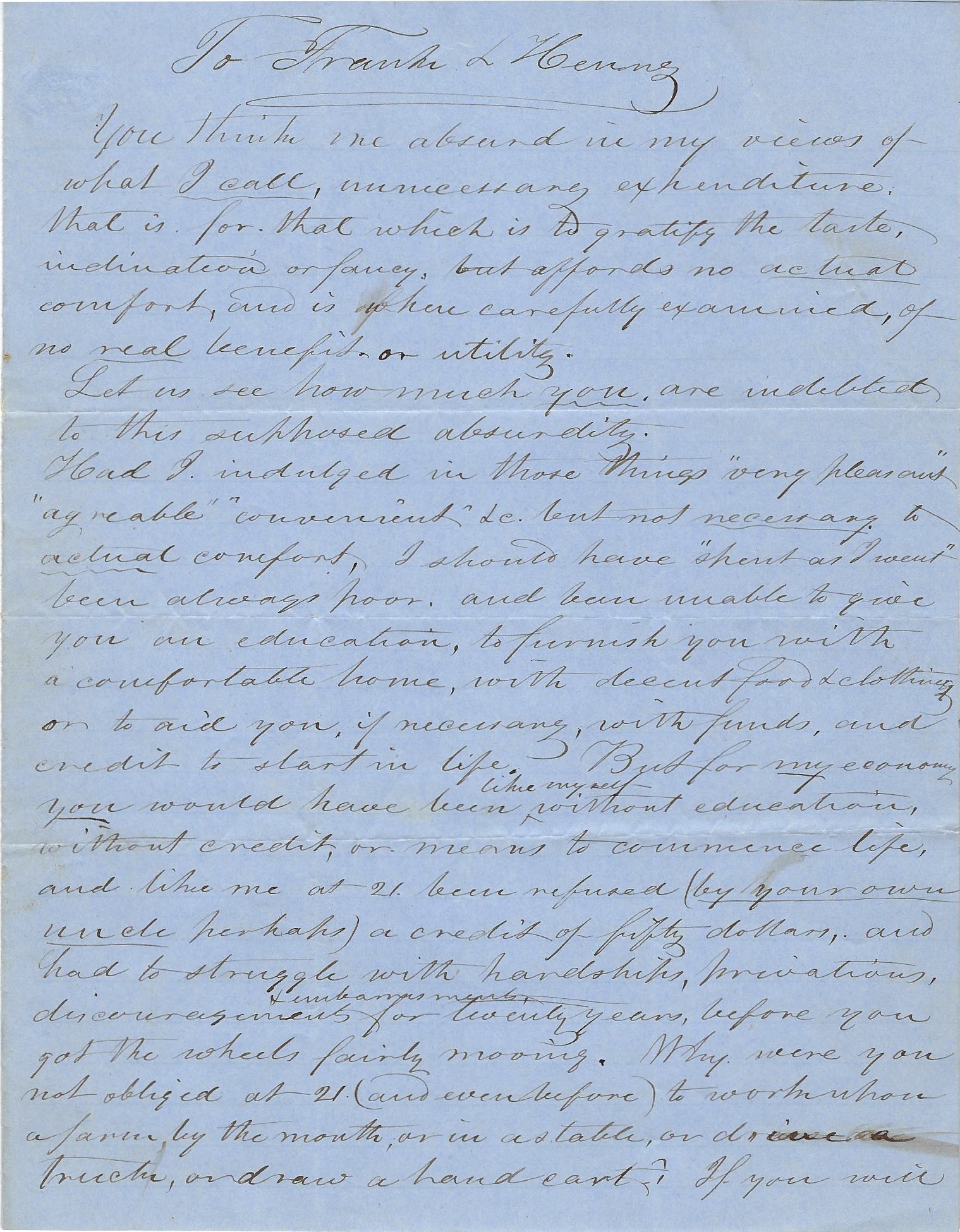

To Frank and Henry

You think me absurd in my views of what I call unnecessary expenditure, that is, for that which is to gratify the taste [or] inclination of fancy, but affords no actual comfort, and is, when carefully examined, of no real benefit or utility.

Let us see how much you are indebted to this supposed absurdity.

Had I indulged in those things “very pleasant” “agreeable” or “convenient” etc. but not necessary to actual comfort, I should have “spent as I went” and been always poor, and been unable to give you an education, to furnish you with a comfortable home, with decent food and clothing, and to aid you, if necessary, with funds and credit to start in life. But for my economy, YOU would have been like myself—without education, without credit, or means to commence life, and like me at 21, been refused (by your own uncle, perhaps) a credit of fifty dollars, and had to struggle with hardships, privations, discouragements, embarrassments for 20 years before you got the wheels fairly moving. Why were you not obliged at 21 (and even before) to work upon a farm by the month, or in a stable, or drive a truck, and now a hand cart? If you’ll examine minutely cause and effect, you will find my habits of economy through life had much to do with it.

Let me illustrate.

Major Chase and Mr McFarland were much better off at 21, both for means of family influence, than myself. But they wanted things “convenient” and “comfortable” “customary” “gratifying” etc. They wished to “live while they did live” “to enjoy themselves” “to do as others do”, etc. And where are they? What have they been able to do for their families, what character, credit or aid can they afford them? What is their own condition for comfort and happiness in their old age? Now seeing, knowing these effects, these results, is it not my duty to warn my family against such evil consequences, to caution them not to be wrecked upon the same rocky shore— even though they laugh at my economy, are annoyed at my admonition and think they can take care of themselves?

Probably the last is true, but how will it be for their children? Shall they have parents who, by the practiced economy, are able to educate, bring them up comfortably, and start them in life with reasonable prospects, or shall through their parents’ indulgence, like Chase and McFarland, be obliged to start struggling with ignorance, poverty and destitution? These are questions for you to answer, and knowing their importance from actual experience and observation, I cannot allow myself to neglect to call your attention to them, though that warning voice may not always be received with satisfaction at the time.

All of us in youth need restraint; my restraint came from necessity. You have not that salutary, though disagreeable, check, and therefore it is more important [that] yours should come from some other source.

By what I have said I would not want to indicate that either of you are practically extravagant, and yet I think both to a certain extent are inclined or have a disposition to be so, but not to so great extent as myself when I was young. Had I been able, I should have gone ahead of either of you. I was compelled to economy and its effect, both in character and property, has proved to me it was the best policy, and that my former notions that I must conform to custom and keep up with the times were all imaginings, all moonshine.

I have said you are inclined, that is you have a pride be as good as others. Well, this desiring is highly praiseworthy, but to be as good, as popular, as much respected as others does not depend on fine clothes, fashionable furniture or ape-ing your neighbors, and if you believe what you often say to me, you have living proof of that constantly before you.

When you get to be forty years old, you will probably need no monitor but your own experience, observation and reflection—until then, one occasionally may do you know harm, and probably no one is more suitable, or will discharge that duty with more fidelity , and with a single eye to your benefit, than your own parents.

With these remarks I close this lecture.

Editors Aside: For anyone contemplating a phone upgrade, amusingly “that which is to gratify the taste [or] inclination of fancy, but affords no actual comfort, and is, when carefully examined, of no real benefit or utility” does in fact pretty much sum up the I-Phone 11 vs 10!