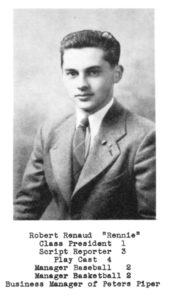

Robert L. Renaud (1925-1945)

When you have an interest in history, sometimes a phone call can send you down a rabbit hole trying to find any information available about someone’s life. That is what happened when I got a call from Martha Boiardi asking if the Historical Society had a photo of Robert L, Renaud, a young man from Southborough who died in World War II. A person in Amsterdam is trying to keep alive the memory of Americans who died fighting to free Europe, and had Robert Renaud’s name, a bit of information, but no photo. He had contacted Martha because she had posted the photo of Robert Renaud’s grave on Find-a-Grave. The internet does provide interesting ways of connecting. Martha’s request set off a search for a photo for the memorial in Amsterdam, but it also made me think that perhaps we here in Southborough should learn a little about this young man.

Robert L. Renaud was born in Hudson on June 30th 1925, the only child of Anna Salo, a Finnish immigrant, and her husband, Charles L. Renaud. The Renaud’s lived on Lincoln Street in Hudson. Robert’s father worked at a shoe factory in Marlborough. His mother worked in Hudson for the Apsley Rubber Company which made gossamer, or rubber, clothing. According to the 1930 Federal Census she made tennis shoes.

The Renaud family moved to Southborough sometime after 1935. Charles, as did so many others in town, worked for Deerfoot Farm. They lived on Newton Street, so it is probable that he worked at the sausage factory. Robert excelled while attending the Southborough schools. At Peters High School he was president of the freshman class, managed the baseball and basketball teams during his sophomore year, was in the senior class play, and wrote for several school publications. Robert was salutatorian of the Peters High School Class of 1943. At graduation in June of 1943, he addressed his 19 fellow graduates, saying “Other years graduates have pondered over what careers they would follow, but this year we have only one choice, for all of us will have the same career – defending our own America against the aggressors who would rob us of the freedom guaranteed by the United States of America.” After summarizing the accomplishments of the “Builders of America” Robert concluded with the words “All of these men and many others, too numerous to mention, have been the builders of America. We wish now to preserve their work by defending America now and by giving to all future Americans the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

These were not empty words to Robert and many of his classmates. Robert enlisted in the Army Air Corps. By the fall of 1943, Robert was in South Carolina at Erskine College as part of one of the special training programs at colleges around the nation that produced “ninety-day wonders,” officers trained quickly to fill the ranks of the rapidly expanding armed forces. He was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant upon completion of the training. After additional training in Nashville, Tennessee, he was stationed in England as a Navigator attached to 452nd Bomber Group, Heavy, 728th Bomber Squadron.

The people back in Southborough and at Peters High School followed his military career and that of many others. The high school publication had a section entitled Alumni News, most of which was filled with news from the young men in the service. Among the names which appeared were names still known in town: Bartolini, Noborini, Salmon, Maley, Finn, Staples, Bagley, Woodward, and Renaud. Robert sent home several articles to the high school publication he had headed while a student. The articles reflected his interest in the aircraft that played such an important role in the war. In an article that he authored, entitled “The P-40 Defends Itself,” he assumed the identity of the oft maligned P-40 fighter plane, and pointed out the P-40 was used in all theaters of the war. Another article that Robert shared was authored by Keith Ayling, and told the story of Reginald Mitchell, “The Man Who Saved Britain, the Creator of the Spitfire.” Robert seemed determined to make the people back home aware of the important role that air power was playing as the war unfolded.

2nd Lieutenant Robert Renaud was the navigator on board a B-17, part of the 728th Bomber Squadron, 452nd Bomber Group. On April 7th, 1945, his plane took off from Deopham Green, Norfolk, England on a mission to Kaltenkirchen, Germany, site of a Luftwaffe airbase. Before reaching its target, the plane came under attack by Messerschmitt 109 fighter planes that succeeded in disabling it and ultimately, according to other pilots, caused it to split in two and explode. Only two parachutes were seen. Seven of the ten crewmen, including Robert L. Renaud were listed as killed in action. Robert was two months shy of his twentieth birthday when he died. On May 8th, 1945, just a month after Robert’s death, Germany surrendered. The 452nd Bomber Group played a key role in bringing about that surrender.

By the time of his death, his parents, Charles and Anna, had moved back to Hudson. It was there that they first received word that their only son was missing in action and later, confirmation that he had been killed. Robert’s grave is in Rural Cemetery here in Southborough, the town where he had spent much of his childhood. His father, Charles, died in 1992. His mother, Anna, died in 1995. They are buried alongside their son at Rural Cemetery.

We remember Robert L. Renaud on this, the 77th anniversary of his death.

Many thanks to Martha Boiardi whose phone call initiated the search for a photo of Robert Renaud and set me off on a path to learn more about him. Martha also shared the information she had been able to uncover. A huge thanks to Patti Fiore who helped me find and dig through the many Peters High School publications where we found the photo, information, and some of Robert’s writings. She also worked her magic to make the photo as clear as possible.