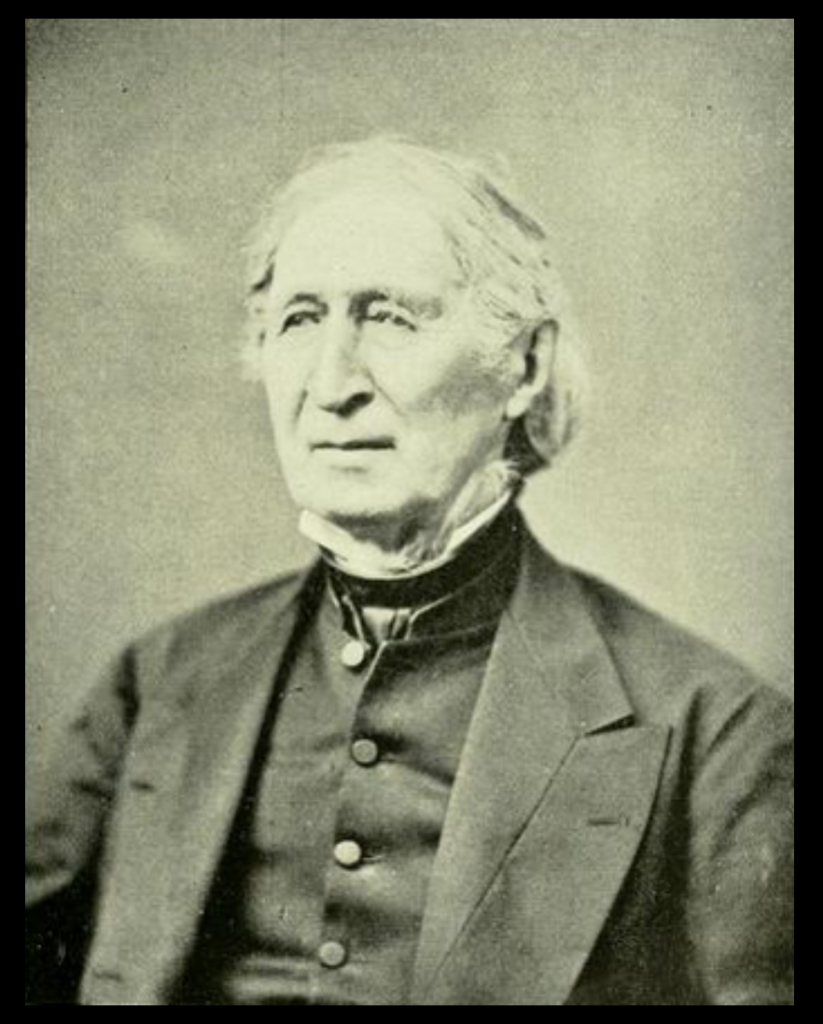

In February 1850, native son Col. Francis B. Fay decided to make a remarkable offer to the citizens of his hometown. He would donate $500 to found a public library for the youth of Southborough, if the citizens would collect or appropriate the same amount. To really appreciate the foresight of this gift, you have to realize that at the time, there were no free libraries in the United States. The libraries that did exist were by subscription only, and many were non-circulating. By the time our free library was founded in 1852, it was just the second in the nation—the Boston Public Library beat us out by a few months.

Secondly while $500 doesn’t seem like much today, adjusted for inflation it’s almost $17,000. But that’s not a terribly accurate way to measure historical amounts. To give you a better idea of Col. Fay’s generosity, $500 in 1850 yields a relative wage of $326,967.21 today. In other words, a job that paid $500 in 1850 would have the equivalent buying power of 326K in 2021. That’s no small potatoes.

Finally, what’s most remarkable to me are the fair-minded stipulations of the gift: both young men and women are to be allowed equal access, and the library may not contain books or materials advocating a particular political or religious view. As Col Fay put it: I trust is will not be understood that I am indifferent to, or unmindful of the importance of religious culture or of political knowledge, but I desire to furnish our youth with the means to qualify themselves to be intelligent, useful and moral citizens, and leave each one at liberty (under the guidance of his parents) to furnish him or herself with the means of religious or political knowledge.

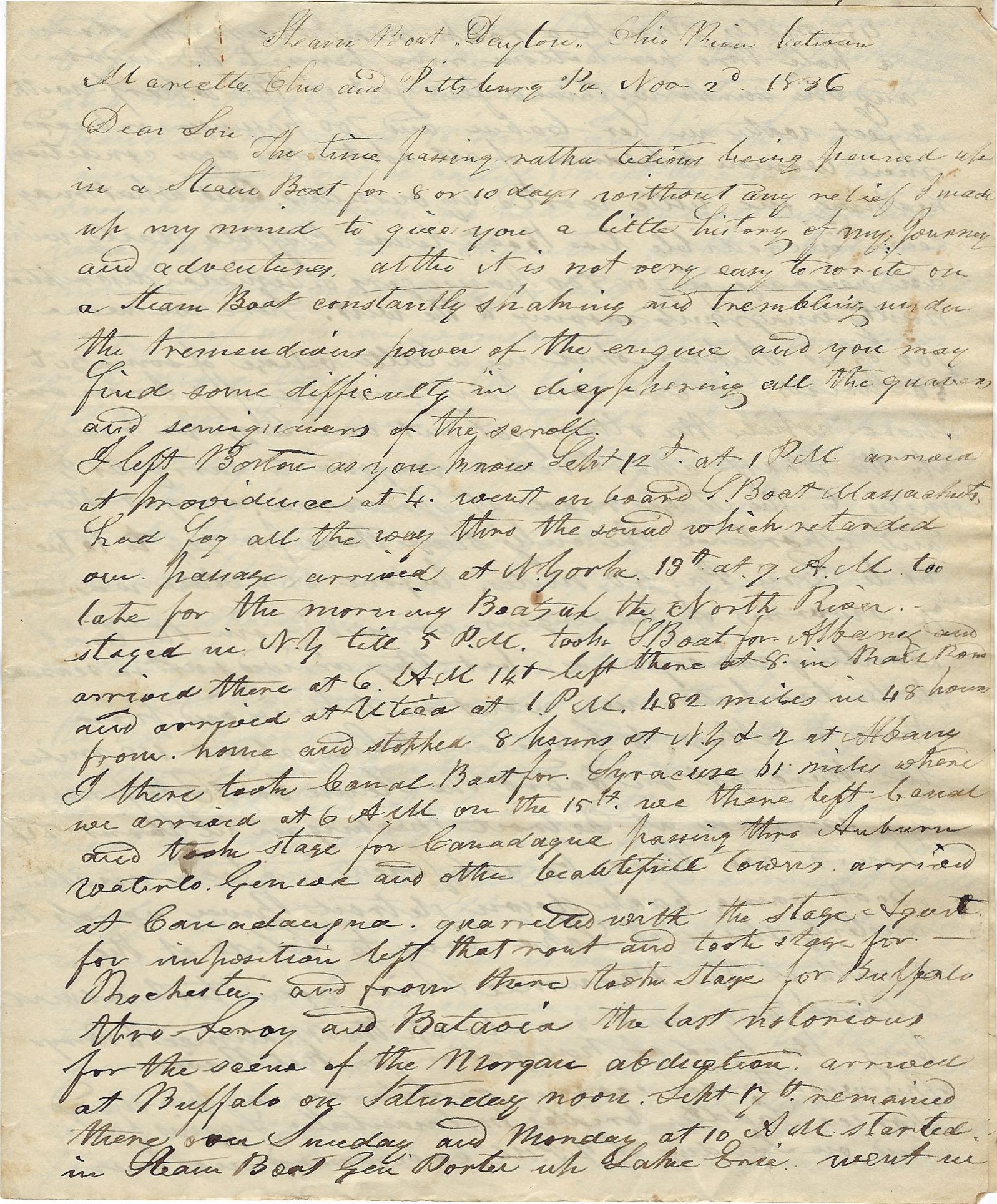

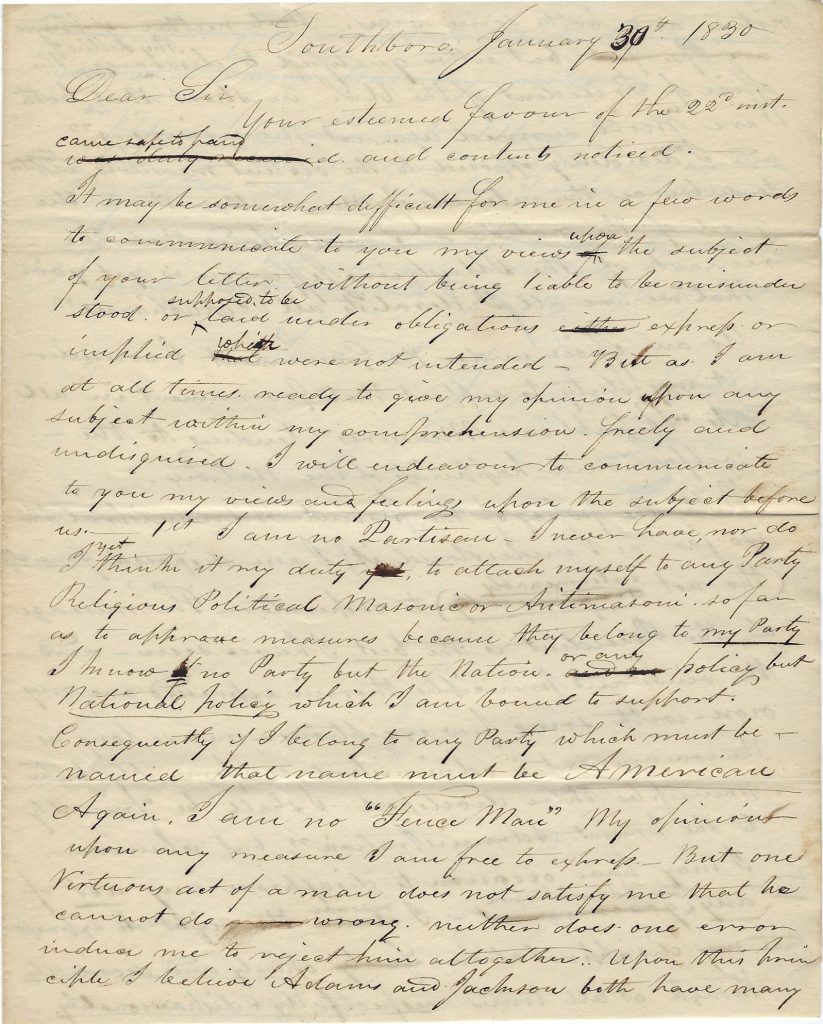

I leave it for you to read the rest of this enlightened offer, just last week transcribed as part of our ongoing work with the papers of Col. Francis B. Fay.

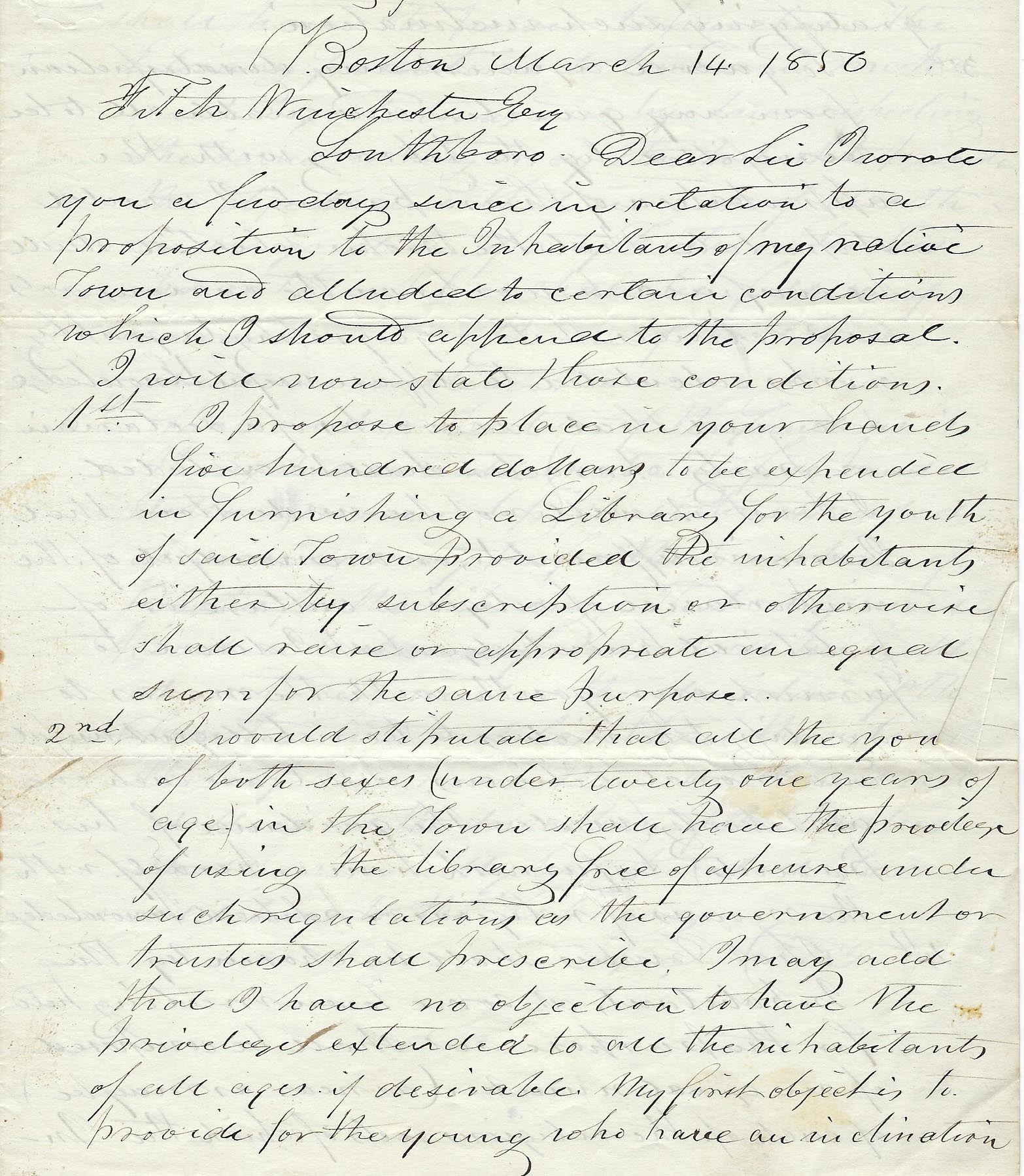

Boston, March 14, 1850

Letter to Fitch Winchester, Esq.

Dear Sir,

I wrote to you a few days since in relation to a proposition to the inhabitants of my native town and alluded to certain conditions which I should append to the proposal. I will now state those conditions.

1st. I propose to place in your hands five hundred dollars to be expended in furnish a library for the youth of said town provided the inhabitants either by subscription of otherwise shall raise or appropriate an equal sum for the same purpose.

2nd. I would stipulate that all the youth of both sexes (under 21 years of age) in the town shall have the privilege of using the library free of expense under such regulations as the government or trustees shall prescribe. I may add that I have no objection to have the privilege extended to all the inhabitants of all ages if desirable. My first object is to provide for the young who have an inclination to acquire useful knowledge the means of gratifying such inclination.

3rd. To guard against any dissatisfaction from any quarter and enable all to be benefited by the library with the approbation of their parents, I would stipulate that the books selected shall be confined to the works on various arts and sciences, history, geography, biography works calculated to diffuse useful knowledge etc. and that all works of a sectarian or party character shall be excluded. I trust is will not be understood that I am indifferent to, or unmindful of the importance of religious culture or of political knowledge, but I desire to furnish our youth with the means to qualify themselves to be intelligent, useful and moral citizens, and leave each one at liberty (under the guidance of his parents) to furnish him or herself with the means of religious or political knowledge.

4th. That trustees shall be chosen by the inhabitants at some town meeting held for the purpose and shall be composed of an equal number (as near as maybe) of each of the religious sects of which the inhabitants are composed, which shall have the power to purchase [for] the library from time to time and make such regulations and by laws respecting the same as they may think best to promote the object and that in the case of death or resignation of any trustee or trustees his or her place shall be filled if convenient with the same denomination.

5th. That such proportion of the fund as is thought advisable (probably five hundred dollars more or less) shall be expended as soon as may be for the purchase of books for the library; that any unexpended funds shall be kept at interest under the direction of the trustees and not less than the interest thereof, nor more than one hundred dollars, at the discretion of the trustees, shall annually be expended for additions to the library.