By Sally Watters

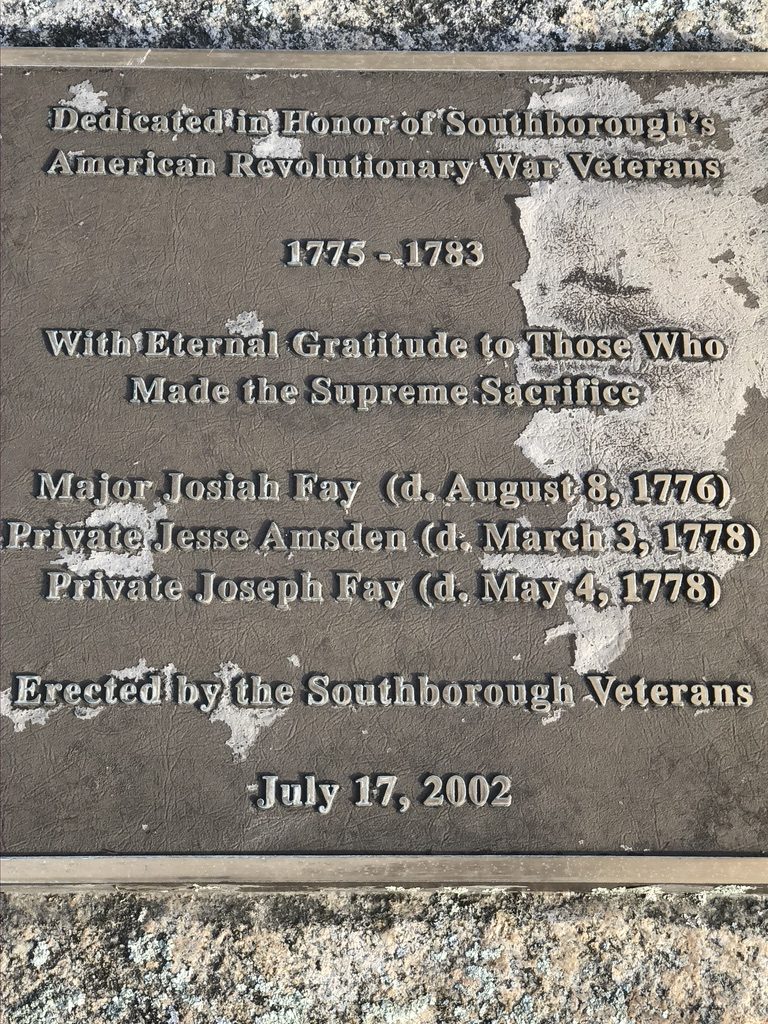

When Michael asked me to take a more active role in writing for this website, I knew I had big shoes to fill. With Patriots Day approaching my plan was to try to learn something about the Revolutionary War veterans who are buried in the Old Burial Ground. In a sense, I wanted to try to put a little flesh on their bones so they would be more than just names. It seemed appropriate to start with the three men from Southborough who had died during the Revolutionary War.

I decided to begin with Jesse Amsden. It is difficult to find a great deal of information about someone who has been dead for almost 250 years. As I began to do research, I discovered that not only had the Amsden family lost the family patriarch, but that four of his sons also joined in the fight for American independence. The family paid a high price for its patriotism. Sadly, I also discovered that preying on the elderly, defrauding the government and government red tape are nothing new. What started as a project to try to learn about Jesse Amsden ended up as the story of five Revolutionary War veterans from the Amsden family. And I have not even gotten to the other two Southborough men who died during the war or the dozens of other Southborough veterans of the Revolutionary War who deserve attention.

Jesse Amsden

Jesse Amsden was born in 1729, the youngest of John and Hannah Howe Amsden’s thirteen children. Jesse was the only one of the thirteen children born in Southborough. His eight brothers and four sisters were all born in Marlborough. The family had not moved, but town lines had when, in 1727, the Stony Brook region of Marlborough was granted permission by the General Court of Massachusetts to form the new Town of Southborough. Jesse’s father John was among the men who had petitioned the state asking that Stony Brook be allowed to separate from Marlborough. John served as a selectman in the newly established town and was a deacon of the church. In 1748, Jesse married Southborough resident Bette Ball with whom he had seven sons and five daughters. When hostilities broke out with England, it did not take Jesse long to become involved. He served as a Private in Captain Ezekiel Knowlton’s Company of Colonel Nicholas Dike’s Massachusetts Infantry Regiment at Dorchester Heights from December 15th 1776 until March 1st 1777.

In May of 1777, shortly before his 48th birthday, Jesse was recruited by Captain Aaron Haynes of Sudbury to enlist in the Continental Army. He was paid a bounty of $20 for enlisting. Jesse was assigned to Captain Haynes Company in the 13th Massachusetts Regiment/6th Continental Regiment under the command of Colonel Edward Wigglesworth. Jesse joined the regiment in July of 1777. Although several of his children were adults at the time of his departure for the Continental Army, his wife Bette was left with seven children at home who ranged in age from 16 to 2. The $20 bounty had probably been an enticing incentive to help with family expenses. Six months after joining the regiment, Jesse died on January 9th, 1778 at Valley Forge. The cause of death was listed as sickness. Jesse was most likely buried in one of the towns near Valley Forge where the sick soldiers were sent. He is not buried in Southborough. His widow Bette seems to disappear from the record books after his death, but several of his children can be tracked.

Jonas and Ephraim Amsden

Four of Jesse’s sons also joined the military during the Revolutionary War. His oldest son Jonas answered the Lexington Alarm of April 19th, 1775. He was a Drummer for Captain Elijah Bellow’s militia company which served for sixteen days. Ephraim, Jesse and Bette’s next son, also answered the Lexington Alarm as a Private in Captain Josiah Fay’s Company which served for five days. Shortly after that service, Ephraim, then a Corporal in Captain Fay’s Company in the regiment commanded by Colonel Jonathan Ward, served from August 1st through October 7th, 1775 at Dorchester Heights. Ephraim, who died in 1819, is buried in an unmarked grave in the Old Burial Ground (OBG). His widow Martha died in 1834 and is also buried in an unmarked grave in the OBG. Jonas Amsden and his wife Hannah moved to Mason, NH after the war and are not buried in the Southborough.

John and Silas Amsden

In March 1781, two of Jesse and Bette’s sons, 18-year-old John and 17-year-old Silas, enlisted in the Continental Army. Silas was described as being 5 feet 11 inches tall with a light complexion. Silas was a Private in Captain John Nutting’s Company in Colonel Job Cushing’s 2nd Massachusetts Regiment. He was discharged in September 1783 after being injured when a load of wood that he was transporting for the garrison at West Point ran over his leg. His knee never healed correctly, leaving him disabled. In April of 1793, Silas Amsden began receiving a pension of $60 a year because of his disability. Silas married Sarah Hemenway of Framingham. In 1797, Silas died in Framingham at the age of 33. The settlement of his estate shows that he was heavily in debt when he died. His creditors were awarded 4 cents on the dollar. Silas is not buried in the OBG. In 1797, the same year that Silas died, his brother John named his newborn son Silas.

John Amsden, described as 5 feet 7 inches tall and of fair complexion, served in Captain Elnathan Haskell’s Company in the regiment commanded by Colonel William Shepard’s. At least part of his service was spent working for the Quartermaster General obtaining supplies. in January 1784 he was discharged by General Henry Knox in New York with the rank of Sargent. Shortly after returning to Southborough, he married Lovisa Bellows. Like his brother Silas, John did not prosper after the war. John and Lovisa had eight children, only three of whom reached adulthood.

In 1819, John applied for a veteran’s service pension stating in his affidavit that he was disabled. He also stated that his three children were sickly and incapable of doing more than light work. An inventory of his possessions at that time showed he owned only three acres of land and had very few personal possessions. He was granted a pension, but after his death in 1827, his widow Lovisa had no means of support. By 1834, both Lovisa and her oldest son, John, had been admitted to the Southborough poorhouse.

The Struggle for a Widow’s Pension

When Congress passed a law in 1836 making the widows of Revolutionary War veterans eligible for pensions, a local man, Larkin Newton, stepped up to help Lovisa apply for a pension. In 1817, early in his career, Larkin Newton had been the school master for the west school district of Southborough. He angered some parents when he severely whipped two students. As a result of the whippings, a special town meeting was called and Mr. Newton was warned to limit his use of physical punishment. The following school year he had moved to the center school district in Southborough where he faced continued concern about his harsh disciplinary methods. He gave up teaching the next year.

From 1837 until his death in 1840, Larkin Newton served as an overseer of the poorhouse. In that position, he was very aware of the poverty faced by Lovisa Amsden and her son John, volunteering to help Lovisa with her application for a widow’s pension. Larkin Newton began to assemble the necessary documents but ran into a problem when no record of John and Lovisa’s marriage could be found. Under the Pension Act of 1836, the widow had to have been married to the veteran while he was still in the military. Larkin Newton submitted statements from several people, including Lovisa’s 85-year-old sister Lucretia Wood of Sherborn, that they were aware of John and Lovisa’s marriage and thought it had taken place in 1782. The pension was approved and by March 1840 the government had sent a total of $720 (about $22,000 today) which included back payments. The very trusting, nearly blind and illiterate Lovisa had placed her X on several documents when requested to do so by Larkin Newton.

A second Pension Act was passed in 1838 allowing pensions for widows who had married a veteran by 1794. Lovisa maintained that she and John had been married in 1784 just after John was discharged from the military, thereby making her eligible for a pension under the 1838 act. Larkin Newton, who had died in September 1840, had told her that under the Pension Act of 1836 she was not eligible to receive a pension. It took several years before people realized that Lovisa had been defrauded by Mr. Newton. Lydia Bellows of Shrewsbury, John’s sister, asked Elijah Clark, a Justice of the Peace who worked to help obtain pensions, to help her brother’s widow Lovisa get a pension.

When Clark corresponded with the War Department, he was shocked to learn that she had already received a pension under the Pension Act of 1836. Lovisa was also surprised. She maintained that she had never received any money from a pension. As documents were assembled and reviewed, people began to suspect that Larkin Newton had forged a number of the documents including one from the Southborough Town Clerk listing the births of Lovisa’s nine children. Her oldest child was listed as Jonathan, born in 1783. The only problem was that Jonathan was a figment of Larkin Newton’s imagination, created in an attempt to show that John and Lovisa had been married before John left the military. In reality, John and Lovisa had only eight children, the oldest of whom was William, born in 1785. Numerous statements from such leading Southborough citizens as Swain Parker, Sullivan Fay and Joel Burnett were sent to the government attesting to the good character of Lovisa, and opining that she would never have tried to defraud the government. Joel Burnett, the town clerk in 1843, sent a statement to the War Department that several old documents dating between 1779 and 1789, had been found in a hitherto misplaced chest.

Among the documents was a paper showing the intentions of marriage for John and Lovisa dated July 1784. That helped establish their marriage, but at the same time created a problem. The government demanded the money that had already been distributed be returned because it had been granted under the Pension Act of 1836 under which she was ineligible. That act required the widow to have been married to the veteran while he was in the military and John and Lovisa’s marriage had taken place after he was discharged. Lovisa’s champions pointed out that whereas she had not been eligible under the Pension Act of 1836, she was eligible under the Pension Act of 1838 so would have received the money anyway.

The government had stopped payments in 1840 when Larkin Newton died so was no longer sending in the necessary paperwork. Lovisa’s supporters thought that at the very least, Lovisa should receive payments from 1840 forward. Lovisa Amsden died in 1846 still a resident in the town poorhouse, without ever receiving any of the widow’s pension to which she was entitled. Her only surviving child, John, attempted to collect the money to which his mother had been entitled. The dispute was still under advisement in 1851, but it appears that the matter was never resolved. John and Lovisa’s son John died in the town poorhouse in 1863. John, the Revolutionary War veteran, and his widow Lovisa are buried in unmarked graves in the Old Burial Ground as are several of their children.

The story of Larkin Newton’s teaching is found in Fences of Stone by Nick Noble.