Happy New Year, History Friends!

This winter we will be researching and digitizing the unpublished papers of Francis B. Fay in our collection, another SHS first.

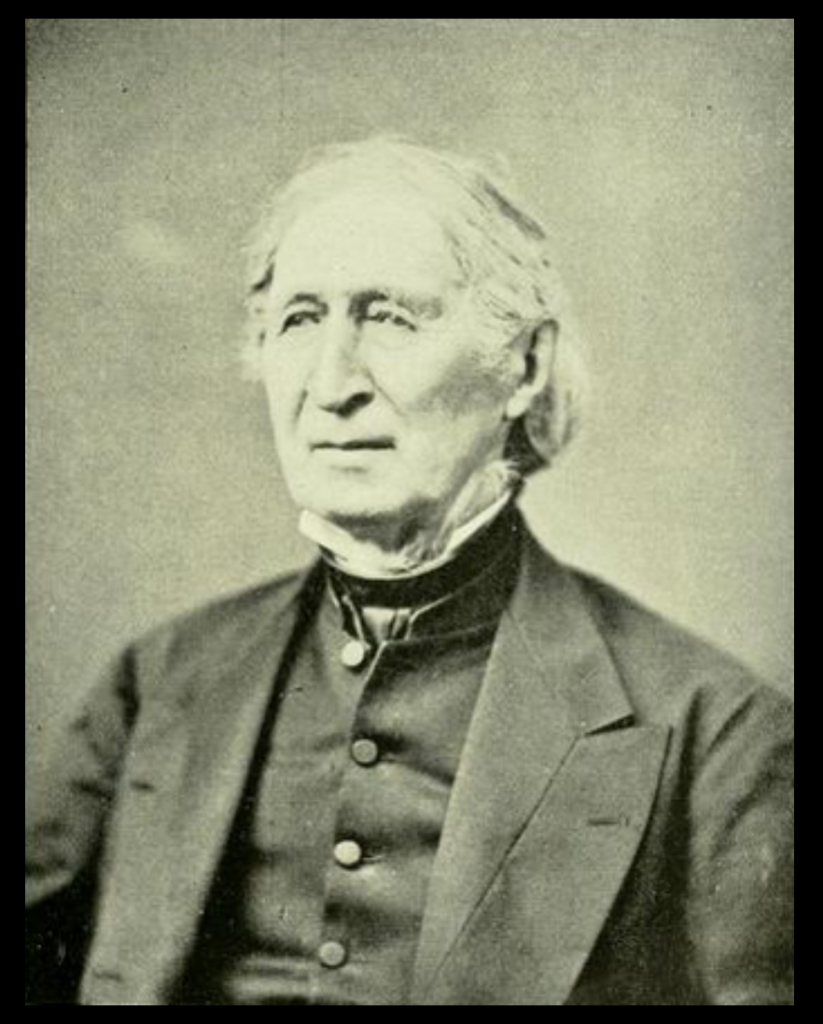

This name may be familiar to you as the founder of our library (the second oldest public library in the nation, btw) but the industrious Col. Fay did more than that single good deed. Born at Southborough in 1793, this remarkable self-made man with little formal education was Southborough Postmaster, Colonel of the Militia, a drover, and a successful merchant, roughly in that order. Seeing an opportunity in what was then the entirely undeveloped area of Chelsea, he acquired the ferry rights from Boston, and was one of the earlier settlers of that area. There he founded a bank, became Chelsea’s first mayor, served in both the state legislature and Congress, and late in life became interested in education for women, helping found one of the first modern reform schools in Lancaster as an alternative to prison, all the while keeping an eye on events of his beloved Southborough.

To give some measure of the man, we present a fascinating letter Fay sent to Jubal Harrington of Worcester while still in Southborough. Harrington’s original letter to Fay is not in our collection, but we can get a pretty good sense of what it might have contained thanks to a fascinating piece in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, detailing a 1850 bombing of Worcester city officials, of which Harrington was later accused:

“Harrington was a lawyer, a former Worcester postmaster, a former state representative and a dedicated foe of the prohibition – temperance movement. He also had a newspaper career. He wrote for Liberty of the Press, a strongly anti-temperance sheet, and edited a weekly, The Worcester Republican, for a while. It was a supporter of Andrew Jackson.

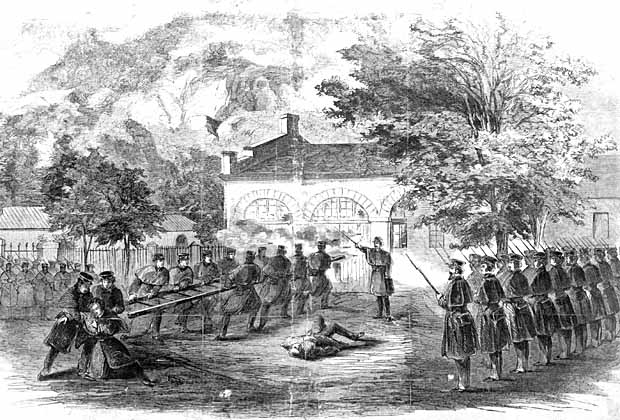

During his term as postmaster, he was embroiled in a counterfeiting scheme, and disappeared from Worcester for a few years. Harrington also was opposed to the anti-slavery, Abolitionist movement that was centered in Worcester, where Eli Thayer was organizing the New England Emigrant Aid Society. It enlisted free men to go to the newly opened territory of Kansas and settle it as a free state in opposition to the slaveholders pouring in from the South.”

So given Harrington’s predilections and subsequent actions, it’s pretty safe to assume that Harrington had probably sent a fiery letter to Fay, trying to rally his fellow postmaster to the Jacksonian cause. Here is Fay’s reply:

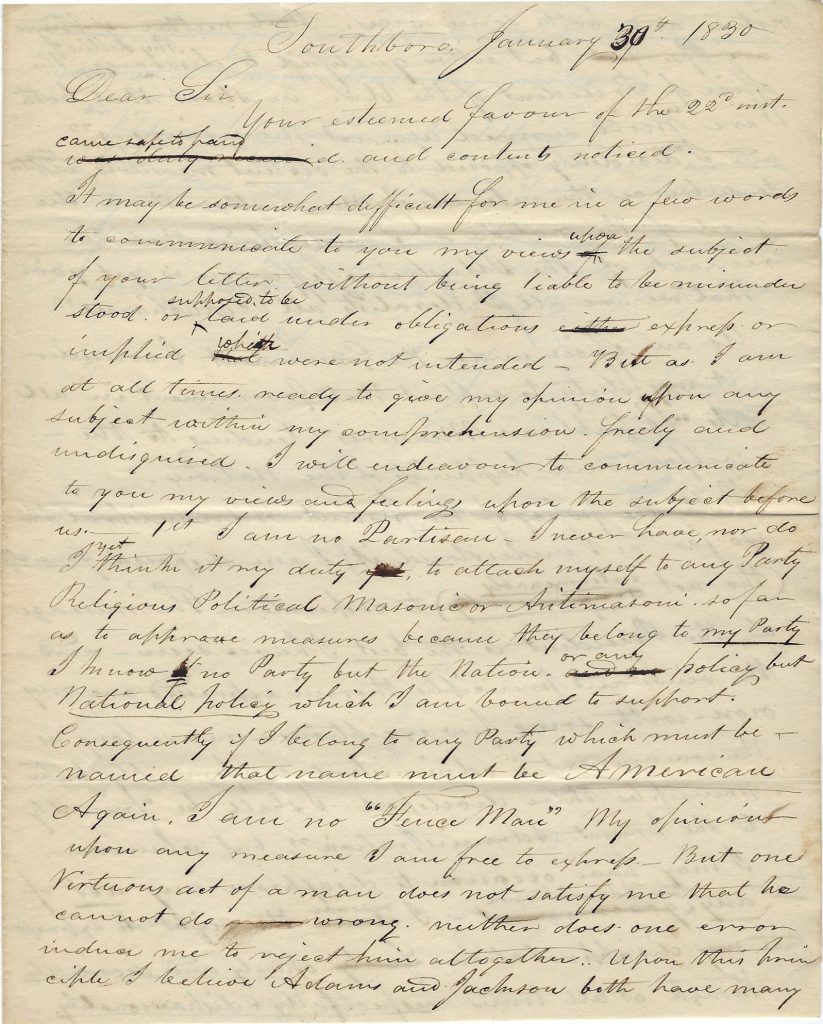

Southborough January 30th 1830

Dear Sir,

Your esteemed favor the 22nd inst. came safe to hand and contents noticed.

(This is 19th-century speak for “your letter of the 22nd of this month duly received and read; “inst.” is an abbreviation for the Latin instante mense, meaning a date of the current month.)

It may be somewhat difficult for me in a few words to communicate to you my views upon the subject of your letter without being liable to be misunderstood or supposed to be laid under obligations express or implied which were not intended. But as I am at all times ready to give my opinion upon any subject within my comprehension freely and undisguised, I will endeavor to communicate to you my views and feelings upon the subject before us.

First, I am no partisan. I never have, nor do I yet think it my duty to attach myself to any party, religious, political, Masonic, anti-Masonic, so far as to approve measures because they belong to my party. I know no party but the nation, or any policy but national policy which I am bound to support. Thus if I belong to any party that must be named, that name must be American. Again, I am no “Fence Man.” My opinion upon any measure I am free to express. But one virtuous act of a man does not satisfy me that he cannot do wrong; neither does one error induce me to reject him altogether. Upon this principle I believe Adams and Jackson both have many virtues and both some vices, but either [is] qualified to discharge the duties of the office of the President of the United States.

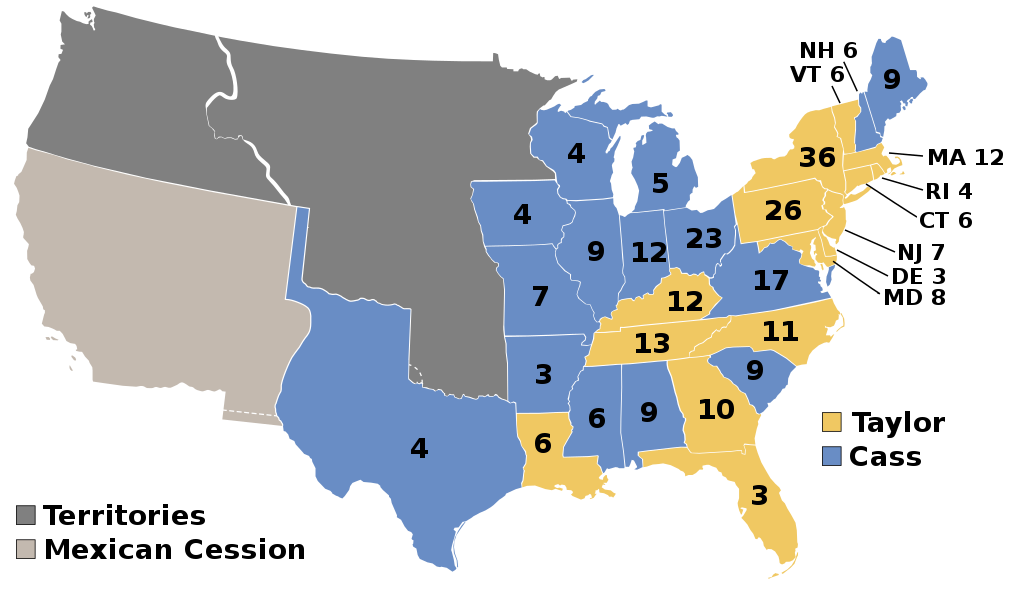

(The election of 1828 had pitted Andrew Jackson against John Quincy Adams—essentially a repeat of the election of 1824, in which no candidate had received a majority of the electoral votes. Therefore the election was decided for Adams by the House of Representatives, according to the 12th Amendment. In 1828, after a bitterly fought rematch, Jackson clearly won the popular and electoral vote, to the disgust of the Federalists.)

In short, both are “more sinned against than sinner” and I am decidedly opposed to the violent measures frequently adopted to subserve the interests of men rather than the good of the nation. I understand that the remark of the illustrious Jefferson is yet good that “we are all Federalists, all Republicans.”

As an officer of the government (Fay was at the time the Soutborough Postmaster) I consider it my duty to support that government in all its “Republican Measures” tending to the welfare and happiness of the nation. With the policy of the present Administration (so far as I understand it) I am disposed generally (though not interminably) to cooperate.

The message of the President is the best I have seen—and the views and principles therein expressed are my own—with some few exceptions—and so long as the government is administered conformably to the principles there developed, I shall be “Friendly to the present Administration,” but whenever I may have occasion to disapprove any act of this or any other Administration, I reserve the right to express my disapprobation openly and decidedly though at all times respectfully and dispassionately.

I have thus hastily endeavored to give you some idea of my political creed— the polar star of which is: “measures are not men.”

In haste, I am respectfully your obedient servant

Francis B Fay

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could all be inspired by Colonel Fay’s advice, and do what’s best for the country regardless of party in this election year?

Who knows—miracles can happen.

Happy New Year Everyone, and please don’t forget to contribute to our annual appeal if you haven’t already.